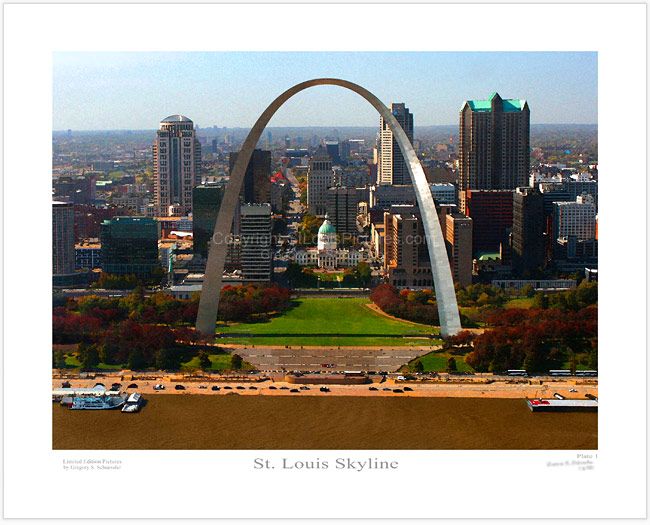

Tonight, Super Bowl 50 -- I suppose they didn't want to use the Roman numeral because, to the NFL, "L" doesn't mean "fifty" or "League," it means "loss" -- is being played at Levi's Stadium in Santa Clara, California, the new home of the San Francisco 49ers.

The 50th Super Bowl should have been played where the 1st one was, at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, which not only still stands, but will be the home of the Los Angeles Rams (and possibly one other team) in the 2016, '17 and '18 season, before the Rams' new stadium opens in Inglewood, and will presumably bring the Super Bowl back to the L.A. area. (The Coliseum hosted 2 Super Bowls, the Rose Bowl in Pasadena 5.)

Why not hold Super Bowl 50 at the site of Super Bowl I? Not enough luxury boxes. Plus, I don't think the NFL is keen on the idea of the fabulously wealthy having to go to the edge of the South Central ghetto.

Neither the Giants nor the Jets reached Super Bowl 50, or even made the Playoffs this season. And neither one visited the Bay Area this season. But, if they had, I would have written something like this:

Before You Go. The San Francisco Bay Area has inconsistent weather. San Francisco, in particular, partly because it’s bounded by water on three sides, is the one city I know of that has baseball weather in football season and football weather in baseball season. Or, as Mark Twain, who worked for a San Francisco newspaper during the Civil War, put it, “The coldest winter I ever spent was a summer in San Francisco.”

The websites of the

San Jose Mercury News and the

Oakland Tribune, and

SFgate.com, the website of the

San Francisco Chronicle, should be checked before you leave. (I won't cite their predictions for today, since it's meaningless for Giant and Jet fans.)

Tickets. The 49ers averaged 70,799 fans per game this season, a sellout every game. They are a team that is struggling now, but they are an iconic franchise, whose new stadium has yet to see its novelty worn off.

So tickets might be hard to come by. You'll probably have to go to the NFL Ticket Exchange. (Don't look up prices for today's game: The Super Bowl has always been overpriced. Even in 1967, it was $12.)

Getting There. It’s 2,906 miles from Times Square in Midtown Manhattan to Union Square in downtown San Francisco, and 2,928 miles from MetLife Stadium to Levi's Stadium. This is the longest Giants or Jets roadtrip there is, and will remain so, unless the clueless Roger Goodell or some future Commissioner decides to put a franchise in London. In other words, if you’re going, you’re flying.

You think I’m kidding? Even if you get someone to go with you, and you take turns, one drives while the other one sleeps, and you pack 2 days’ worth of food, and you use the side of the Interstate as a toilet, and you don’t get pulled over for speeding, you’ll still need over 2 full days. Each way.

But, if you really, really want to drive... Get onto Interstate 80 West in New Jersey, and – though incredibly long, it’s also incredibly simple – you’ll stay on I-80 for almost its entire length, which is 2,900 miles from Ridgefield Park, just beyond the New Jersey end of the George Washington Bridge, to the San Francisco end of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge.

If you're driving directly to Santa Clara (i.e., if your hotel is there), then, getting off I-80, you’ll need Exit 8A for I-880, the Nimitz Freeway – the 1997-rebuilt version of the double-decked expressway that collapsed, killing 42 people, during the Loma Prieta Earthquake that struck during the 1989 World Series between the 2 Bay Area teams. From I-880, you’ll take Exit 8A, for Great Mall Parkway.

Not counting rest stops, you should be in New Jersey for an hour and a half, Pennsylvania for 5:15, Ohio for 4 hours, Indiana for 2:30, Illinois for 2:45, Iowa for 5 hours, Nebraska for 7:45, Wyoming for 6:45, Utah for 3:15, Nevada for 6:45, and California for 3:15. That’s almost 49 hours, and with rest stops, and city traffic at each end, we’re talking 3 full days.

That’s still faster than Greyhound and Amtrak. Greyhound does stop in Oakland, at 2103 San Pablo Avenue at Castro Street. But the trip averages about 80 hours, depending on the run, and will require you to change buses 2, 3, 4 or even 5 times. And you'd have to leave no later than Thursday morning to get there by Sunday gametime. Round-trip fare is $592, but it can drop to $396 with advanced purchase.

On Amtrak, to make it in time for a Sunday afternoon kickoff, you would leave Penn Station on the

Lake Shore Limited at 3:40 PM on Wednesday, arrive at Union Station in Chicago at 9:45 AM Central Time on Thursday, and switch to the

California Zephyr at 2:00 PM, arriving at Emeryville, California at 4:10 PM Pacific Time on Saturday. Round-trip fare: $673. Then you'd have to get to downtown San Francisco or San Jose.

Getting back, the

California Zephyr leaves Emeryville at 9:10 AM, arrives in Chicago at 2:50 PM 2 days later, and the

Lake Shore Limited leaves at 9:30 PM and arrives in New York at 6:23 PM the next day. So we're talking a Thursday to the next week's Thursday operation by train.

Newark to San Francisco is a relatively cheap flight, considering the distance. You can get a round-trip fare for under $600. You'd have to change planes once on the way to San Francisco, and then taking BART into the city. BART from SFO to downtown San Francisco takes 30 minutes, and it's $8.65.

Once In the City. San Francisco was settled in 1776, and named for St. Francis of Assisi. San Jose was settled the next year, and named for Joseph, Jesus' earthly father. Both were incorporated in 1850. Santa Clara was settled in 1777 and incorporated in 1852. It was named after St. Clare of Assisi, one of St. Francis' 1st followers. Oakland was also founded in 1852, and named for oak trees in the area.

With the growth of the computer industry, San Jose has become the largest city in the San Francisco Bay Area, with a little over 1 million people. San Francisco has about 850,000, Oakland 400,000, and Santa Clara, the new home of the 49ers, 120,000. Overall, the Bay Area is home to 8.6 million people and rising, making it the 4th largest metropolitan area in North America, behind New York with 23 million, Los Angeles with 18 million, and Chicago with just under 10 million.

San Francisco doesn't really have a "city centerpoint," although street addresses seem to start at Market Street, which runs diagonally across the southeastern sector of the city, and contains the city's 8 stops on the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) subway system. Most Oakland street addresses aren't divided into north-south, or east-west. The city does have numbered streets, starting with 1st Street on the bayfront and increasing as you move northeast. One of the BART stops in the city is called "12th Street Oakland City Center," and it's at 12th & Broadway, so if you're looking at a centerpoint for the city, that's as good as any. San Jose's street addresses are centered on 1st Street and Santa Clara Street.

A BART train

A BART ride within San Francisco is $1.75; going from downtown to Daly City, where the Cow Palace is, is $3.00; going from downtown SF to downtown Oakland is $3.15, and from downtown SF to the Oakland Coliseum complex is $3.85. In addition to BART, CalTrain and ACE -- Altamont Commuter Express -- link the Peninsula with San Francisco and San Jose.

The sales tax in California is 6.5 percent, and it rises to 8.75 percent within the City of San Francisco and the City of San Jose. It's 9 percent in Alameda County, including the City of Oakland. In San Francisco, food and pharmaceuticals are exempt from sales tax. (Buying marijuana from a street dealer doesn't count as such a "pharmaceutical," and pot brownies wouldn't count as such a "food." Although he probably wouldn't charge sales tax -- then again, it might be marked up so much, the sales tax would actually be a break.)

Important to note: Do not call San Francisco "Frisco." They hate that. "San Fran" is okay. And, like New York (sometimes more specifically, Manhattan), area residents tend to call it "The City." For a time, the Golden State Warriors, then named the San Francisco Warriors, actually had "THE CITY" on their jerseys. They will occasionally bring back throwback jerseys saying that.

Going In. The official address of Levi's Stadium is 4900 Marie P. DeBartolo Way, after the mother of former 49ers owner and newly-elected Pro Football Hall-of-Famer Eddie DeBartolo. (If you're going to apply to the U.S. Postal Service to make it 4900, why not 4949?) The intersection is Marie P. DeBartolo Way and Tasman Drive. It's 46 miles southeast of downtown San Francisco, 39 miles southeast of downtown Oakland, and 9 miles northwest of downtown San Jose.

If you're driving in, parking is $30. There is plenty of room for tailgating, and 49er fans have been known to have, shall we say, more refined tailgate party palates. You're as likely to find wine as beer, fancy French cheeses as Cheese Whiz, and sushi as bratwurst.

If you’re taking public transportation, you take ACE, Altamont Commuter Express, from downtown San Francisco to Santa Clara station. California's Great America theme part is next-door. From downtown San Jose, take the 916 trolley.

Naming rights to the stadium were bought by Levi Strauss & Company, the San Francisco-based clothing giant that popularized blue jeans all over the world. I'm against corporate names on stadiums and arenas, but if you're going to put one on a Bay Area stadium, that's as good a choice as any.

The field runs north-to-south (well, northwest-to-southeast), and is real grass. It hosts the Pacific-12 Conference Championship Game, and in 2019 (for the 2018 season) it will host the College Football Playoff National Championship.

The NHL hosted a Stadium Series outdoor hockey game there a year ago, with the San Jose Sharks losing to their arch-rivals, the Los Angeles Kings. It is contracted to host 1 San Jose Earthquakes game per year, and last year Manchester United beat Barcelona there. It will host games of the 2016 Copa America. The stadium's largest crowd was 76,976, for WrestleMania 31 last year. Coldplay is playing the Super Bowl halftime show, and they will return to the stadium in September. One Direction and Taylor Swift have both played it.

Food. San Francisco, due to being a waterfront city and a transportation and freight hub, has a reputation as one of America’s best food cities.

Levi's Stadium benefits from this:.

Centerplate, which will be handling most of the stadium's concessions, boasts that they'll have one food and beverage point of sale for every 86 fans, cutting down on line times. And if you're a vegan or vegetarian, you'll be particularly excited to hear that the stadium will have the best meatless options in the NFL.Over 180 different food items will be served at Levi's Stadium, with 17 types of quick-service concepts that will be named for exactly what they're selling. They include Franks (nitrate-free, with a vegan option), Burgers (with American Kobe beef and vegan burgers), Curry (Indian-style, with spiced naan, cassava chips, and varieties like Rajisthani lamb and vegan navy bean and kale), Tortas, Soft Serve, Barbecue (pulled pork or pulled jackfruit), Panini and Steamed Buns (Asian-style bao in Peking duck, pork belly, and vegan portobello varieties).

All the menus will be on digital screens, and AT&T Park regulars will find familiar favorites like garlic fries and Ghirardelli ice-cream sundaes. All told, there are 14 vegan and 26 vegetarian food options (though the latter figure includes a few types of ice cream). 13 of the 36 stands will offer kid's meals, with a choice of pizza, hot dogs, or chicken tenders.

In addition to the standard quick-service offerings, the stadium will feature an outpost of Santa Cruz's Mondo Burrito on the upper concourse, and a tap room at the 50-yard line with 42 different drafts (most of which are from Anheuser-Busch, but with some bigger craft options like Lagunitas IPA, Speakeasy Prohibition, 21st Amendment Brew Free or Die, and, in a coup for small SOMA upstart Cellarmaker, Dobis Pale Ale).

Aiden Winery's kegged chardonnay and pinot noir will be on tap throughout the stadium, with another 12 or so wines from local producers scattered here and there.

Team History Displays. The 49ers have made the Playoffs 26 times, most recently in 2013. They've won the NFC West 19 times: In 1970, '71, '72, '81, '83, '84, '86, '87, '88, '89, '90, '92, '93, '94, '95, '97, 2002, '11 and '12. They've won 6 NFC Championships: in 1981, '84, '88, '89, '94 and 2012. And they've won 5 Super Bowls: XVI in 1981-82, XIX in 1984-85, XXIII in 1988-89, XXIV in 1989-90, and XXIX in 1994-95. But there appears to be no notations for any of these inside Levi's Stadium.

The 49ers have retired 12 numbers, plus notations for former owner Eddie DeBartolo and the late former head coach Bill Walsh:

* From the 1957 team that tied for the NFL Western Division title, but lost a Playoff to the Cleveland Browns: 34, running back Joe Perry; 39, running back Hugh McElhenny; 73, defensive tackle Leo Nomellini; and 79, offensive tackle Bob St. Clair. Quarterback Y.A. Tittle also played for this team, but his Number 14 has not been retired by the 49ers. (It has been retired by the Giants.) Nor has the Number 35 of John Henry Johnson, who left the 49ers the season before. Tittle, Perry, McElhenny and Johnson formed the only all-Hall-of-Fame backfield ever (playing in San Francisco from 1954 to '56).

* From the 1970 and '71 teams that reached back-to-back NFC Championship Games, losing both to the Dallas Cowboys: 12, quarterback John Brodie; 37, cornerback Jimmy Johnson (no relation to the Cowboy coach of the same name, or to John Henry Johnson); and 70, defensive tackle Charlie Krueger. Brodie is not in the Hall of Fame. Linebacker Dave Wilcox is, but his Number 64 has not been retired.

* From the Super Bowl XVI and XIX winners: DeBartolo and Walsh; 16, quarterback Joe Montana; 42, cornerback Ronnie Lott; 87, receiver Dwight Clark. Clark is not in the Hall of Fame. Defensive end Mean Fred Dean is, but his Number 74 has not been retired. Also not in the Hall of Fame, but should be, is Number 33, running back Roger Craig.

* From the Super Bowl XXIII and XXIV winners: DeBartolo, Walsh, Montana, Lott; 80, receiver Jerry Rice. Craig was still there. Linebacker Charles Haley also was, and is in the Hall, but his Number 94 has not been retired. Steve Young was a backup, and while he got 2 rings, he barely played.

* From the Super Bowl XXIX winners: DeBartolo and Rice; 8, quarterback Steve Young. Linebacker Rickey Jackson, a Hall-of-Famer for his service to the New Orleans Saints, was on this team. So was defensive end Richard Dent, one for his service to the Chicago Bears. So was cornerback Deion Sanders, whose best years were with the Atlanta Falcons and Dallas Cowboys.

* No players from the 2012 NFC Championship have yet been honored.

The 49ers also have a team Hall of Fame, whose inductees include: DeBartolo, Walsh, Young, Brodie, Tittle, Montana, Craig, Perry, both Johnsons, McElhenny, Lott, Wilcox, Krueger, Nomellini, Dean, St. Clair, Rice; founding owners Tony and Vic Morabito, 1950s receiver Gordy Soltau (Number 82), 1960s cornerback R.C. Owens (27), Super Bowl XXIV- and XXIX-winning coach George Seifert, and 1980s and '90s executive John McVay -- whom Giant fans might remember as the head coach who was fired after the 1978 "Miracle of the Meadowlands" game against the Philadelphia Eagles.

The Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame (BASHOF) is unusual in that its exhibits are spread over several locations, including Levi's Stadium. The 49ers honored include Walsh, DeBartolo, Brodie, Tittle, Montana, Craig, Perry, both Johnsons, McElhenny, Lott, Wilcox, Nomellini, St. Clair, Rice, Soltau, 1940s and '50s coach Buck Shaw, 1940s quarterback Frankie Albert (Number 16, the NFL's 1st great lefthanded quarterback, long before Young), 1970s quarterback Jim Plunkett (16, a San Jose native elected mainly on his performance with the Raiders), 1980s and '90s tight end Brent Jones (84), and a San Francisco native who closed his career with the 49ers, but is now far better known for something else: O.J. Simpson.

Stuff. The 49ers' flagship team store is inside Gate A of Levi's Stadium. They also have team stores throughout the Bay Area.

As a historic team, there are lots of books written about the Niners. In 2014, Brian Murphy -- putting team owner Jed York (Eddie DeBartolo's son-in-law)'s name on it to gain inside access -- published San Francisco 49ers: From Kezar to Levi's Stadium. A few months earlier, Matt Maiocco and team legend Dwight Clark collaborated on San Francisco 49ers: The Complete Illustrated History.

Last year, Dave Newhouse published Founding 49ers: The Dark Days Before the Dynasty. After the 4th Super Bowl win in 1990, Bill Walsh got together with San Francisco Chronicle writer Glenn Dickey and wrote Building a Champion: On Football and the Making of the 49ers, the ultimate inside look at the greatest football organization of the past 35 years. (Yes, ahead of the Patriots of the last 15 years: The 49ers won more Super Bowls, and they didn't have to cheat.)In 1990, the NFL put out

San Francisco 49ers: Team of the '80s. It's now out on DVD. In 2006, in time for the team's 60th Anniversary (this coming year is the 70th), the League put out

San Francisco 49ers: The Complete History. With another Super Bowl appearance and a new stadium, it's no longer so complete, but it's the best video history of the team available.

During the Game. This is not a Raider game, where people come dressed as pirates, biker gangsters, Darth Vader, the Grim Reaper, and so on. Nor is this a Giant game where you might be wearing Dodger gear. This is a 49ers game, where fans have tailgated with picnic tables, tablecloths, and even candlesticks -- and not just because they once played at Candlestick Park. These people are as likely to drink California wine as Wisconsin beer at their tailgates. They are more refined, and for all their success, they're not particularly arrogant. You will be safe wearing your Giant or Jet colors.

The 49ers hold auditions for National Anthem singers, instead of having a regular. Since the 1980s, "We're the 49ers" has been the team's theme song. Before that, they had a "Touchdown, 49ers" fight song. The 49ers were named for the Gold Rush prospectors that made Northern California possible in 1849, and their mascot resembles one of them, named Sourdough Sam, as sourdough bread was, long before Rice-a-Roni, the actual "San Francisco treat." Naturally, he wears Number 49.

After the Game. Again, Niner fans are not Raider fans. And the Santa Clara stadium is far from any crime issues. Don't antagonize anyone, and you'll be fine.

If you want to go out for a postgame meal or drinks, David's Restaurant, across Tasman Drive from the stadium's north end, is described as a "traditional American restaurant." But it's part of the Santa Clara Country Club, so it might be a bit expensive. A little bit east on Tasman, Butter & Zeus sells fast-food sandwiches and salads. Giovanni's New York Pizzeria is 4 miles to the west, at 1127 Lawrence Expressway (it's really just a suburban divided highway), but I can't say that its "New York pizza" is authentic.

There are three bars in the Lower Nob Hill neighborhood of San Francisco that are worth mentioning. Aces, at 998 Sutter Street & Hyde Street in San Francisco’s Lower Nob Hill neighborhood, is said to have a Yankee sign out front and a Yankee Fan as the main bartender. It’s also the home port of Mets, NFL Giants, Knicks and Rangers fans in the Bay Area.

R Bar, at 1176 Sutter & Polk Street, is the local Jets fan hangout. And Greens Sports Bar, at 2239 Polk at Green Street, is also said to be a Yankee-friendly bar. Of course, you’ll have to cross the Bay by car or by BART to get there.

Sidelights. The San Francisco Bay Area, including the East Bay (which includes Oakland), has a very rich sports history. Here are some of the highlights:

* AT&T Park. Home of the Giants since 2000, it has been better for them than Candlestick -- aesthetically, competitively, financially, you name it. Winning 3 World Series since it opened, it's been home to The Freak (Tim Lincecum) and The Steroid Freak (Barry Bonds).

It's hosted some college football games, and a February 10, 2006 win by the U.S. soccer team over Japan. 24 Willie Mays Plaza, at 3rd & King Streets.

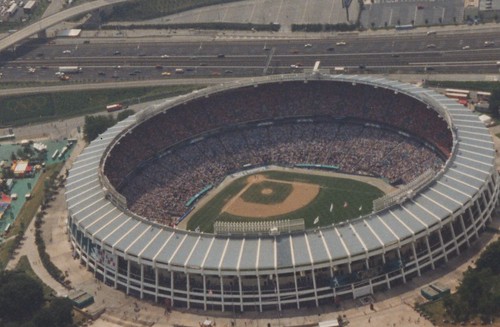

* Oakland Coliseum complex. This includes the stadium that has been home to the A’s since 1968 and to the NFL’s Oakland Raiders from 1966 to 1981 and again since 1995; and the Oracle Arena, a somewhat-renovated version of the Oakland Coliseum Arena, home to the NBA’s Golden State Warriors on and off since 1966, and continuously since 1971 except for a one-year hiatus in San Jose while it was being renovated, 1996-97. Various defunct soccer teams played at the Coliseum, and the Bay Area’s former NHL team, the Oakland Seals/California Golden Seals, played at the arena from 1967 to 1976.

The Oakland Coliseum Arena opened on November 9, 1966, and became home to the Warriors in 1971 -- at which point they changed their name from "San Francisco Warriors" to "Golden State Warriors," as if representing the entire State of California had enabled the "California Angels" to take Los Angeles away from the Dodgers, and it didn't take L.A. away from the Lakers, either.

The arena also hosted the Oakland Oaks, who won the American Basketball Association title in 1969; the Oakland Seals, later the California Golden Seals (didn't work for them, either), from 1967 to 1976; the Golden Bay Earthquakes of the Major Indoor Soccer League; and select basketball games for the University of California from 1966 to 1999. It's also been a major concert venue, and hosted the Bay Area's own, the Grateful Dead, more times than any other building: 66. Elvis Presley sang at the Coliseum Arena on November 10, 1970 and November 11, 1972.

In 1996-97, the arena was gutted to expand it from 15,000 to 19,000 seats. (The Warriors spent that season in San Jose.) This transformed it from a 1960s arena that was too small by the 1990s into one that was ready for an early 21st Century sports crowd. It was renamed The Arena in Oakland in 1997 and the Oracle Arena in 2005. The Warriors plan to move into a new arena in San Francisco for the 2017-18 season.

* Seals Stadium. Home of the PCL’s San Francisco Seals from 1931 to 1957, the Mission Reds from 1931 to 1937, and the Giants in 1958 and ’59, it was the first home professional field of the DiMaggio brothers: First Vince, then Joe, and finally Dom all played for the Seals in the 1930s. The Seals won Pennants there in 1931, ’35, ’43, ’44, ’45, ’46 and ’57 (their last season). It seated just 18,500, expanded to 22,900 for the Giants, and was never going to be more than a stopgap facility until the Giants’ larger park could be built. It was demolished right after the 1959 season, and the site now has a Safeway grocery store.

Bryant Street, 16th Street, Potrero Avenue and Alameda Street, in the Mission District. Hard to reach by public transport: The Number 10 bus goes down Townsend Street and Rhode Island Avenue until reaching 16th, but then it’s an 8-block walk. The Number 27 can be picked up at 5th & Harrison Streets, and will go right there.

* Candlestick Park. Home of the Giants from 1960 to 1999, the NFL 49ers since 1970, and the Raiders in the 1961 season, this may have been the most-maligned sports facility in North American history. Its seaside location (Candlestick Point) has led to spectators being stricken by wind (a.k.a. The Hawk), cold, and even fog. It was open to the Bay until 1971, including the 1962 World Series between the Yankees and the Giants, and was then enclosed to expand it from 42,000 to 69,000 seats for the Niners. It also got artificial turf for the 1970 season, one of the first stadiums to have it – though, to the city’s credit, it was also the 1st NFL stadium and 2nd MLB stadium (after Comiskey Park in Chicago) to switch back to real grass.

The Giants only won 2 Pennants there, and never a World Series. But the 49ers have won 5 Super Bowls while playing there, with 3 of their 6 NFC Championship Games won as the home team. The NFL Giants did beat the 49ers in the 1990 NFC Championship Game, scoring no touchdowns but winning 15-13 thanks to 5 Matt Bahr field goals. The Beatles played their last “real concert” ever at the ‘Stick on August 29, 1966 – only 25,000 people came out, a total probably driven down by the stadium’s reputation and John Lennon’s comments about religion on that tour.

The Giants got out, and the 49ers have now done the same, with their new stadium opening last year. The last sporting event was a U.S. national soccer team win over Azerbaijan earlier this year, the 4th game the Stars & Stripes played there (2 wins, 2 losses). It has now been demolished, and good riddance.

Best way to the site by public transport isn’t a good one: The KT light rail at 4th & King Streets, at the CalTrain terminal, to 3rd & Gilman Streets, and then it’s almost a mile’s walk down Jagerson Avenue. So unless you’re driving/renting a car, or you’re a sports history buff who HAS to see the place, I wouldn’t suggest making time for it.

In spite of the Raiders' return, the 49ers are more popular -- according to

a 2014 Atlantic Monthlyarticle, even in Alameda County. The Raiders remain more popular in the Los Angeles area, a holdover from their 1982-94 layover, and also a consequence of L.A. not having had a team since.

* Kezar Stadium. The 49ers played here from their 1946 founding until 1970, the Raiders spent their inaugural 1960 season here, and previous pro teams in the city also played at this facility at the southeastern corner of Golden Gate Park, a mere 10-minute walk from the fabled corner of Haight & Ashbury Streets. High school football, including the annual City Championship played on Thanksgiving Day, used to be held here as well. Bob St. Clair, who played there in high school, college (University of San Francisco) and the NFL in a Hall of Fame career with the 49ers, has compared it to Chicago’s Wrigley Field as a “neighborhood stadium.” After the 49ers left, it became a major concert venue.

The original 60,000-seat structure was built in 1925, and was torn down in 1989 (a few months before the earthquake, so there’s no way to know what the quake would have done to it), and was replaced in 1990 with a 9,000-seat stadium, much more suitable for high school sports. The original Kezar, named for one of the city’s pioneering families, had a cameo in the Clint Eastwood film

Dirty Harry. Frederick & Stanyan Streets, Kezar Drive and Arguello Blvd. MUNI light rail N train.

* Emeryville Park. Also known as Oaks Park, this was the home of the Pacific Coast League’s Oakland Oaks from 1913 until 1955. The Oaks won Pennants there in 1927, ’48, ’50 and ’54.

Most notable of these was the 1948 Pennant, won by a group of players who had nearly all played in the majors and were considered old, and were known as the Nine Old Men (a name often given to the U.S. Supreme Court). These old men included former Yankee 1st baseman Nick Etten, the previous year’s World Series hero Cookie Lavagetto of the Brooklyn Dodgers (an Oakland native), Hall of Fame catcher Ernie Lombardi (another Oakland native), and one very young player, a 20-year-old 2nd baseman from Berkeley named Billy Martin. Their manager? Casey Stengel. Impressed by Casey’s feat of managing the Nine Old Men to a Pennant in a league that was pretty much major league quality, and by his previously having managed the minor-league version of the Milwaukee Brewers to an American Association Pennant, Yankee owners Dan Topping and Del Webb hired Casey to manage in 1949. Casey told Billy that if he ever got the chance to bring him east, he would, and he was as good as his word.

Pixar Studios has built property on the site. 45th Street, San Pablo Avenue, Park Avenue and Watts Street, Emeryville, near the Amtrak station. Number 72 bus from Jack London Square.

* Frank Youell Field. This was another stopgap facility, used by the Raiders from 1962 to 1965, a 22,000-seat stadium that was named after an Oakland undertaker – perhaps fitting, although the Raiders didn’t yet have that image. Interestingly from a New York perspective, the first game here was between the Raiders and the forerunners of the Jets, the New York Titans.

It was demolished in 1969. A new field of the same name was built on the site for Laney College. East 8th Street, 5th Avenue, East 10th Street and the Oakland Estuary. Lake Merritt BART station.

* Cow Palace. The more familiar name of the Grand National Livestock Pavilion, this big barn just south of the City Line in Daly City has hosted just about everything, from livestock shows and rodeos to the 1956 and 1964 Republican National Conventions. (Yes, the Republicans came here, not the “hippie” Democrats, although they did hold their 1984 Convention downtown at the George Moscone Convention Center.)

The ’64 Convention is where New York’s Governor Nelson Rockefeller refused to be booed off the podium when he dared to speak out against the John Birch Society – the Tea Party idiots of their time – and when Senator Barry Goldwater was nominated, telling them, “I would remind you, my fellow Republicans, that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice! And I would remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” (Personally, I think that extremism in the defense of liberty is no defense of liberty.)

Built in 1941, it is one of the oldest remaining former NBA and NHL sites, having hosted the NBA’s Warriors (then calling themselves the San Francisco Warriors) from 1962 to 1971, the NHL’s San Jose Sharks from their 1991 debut until their current arena could open in 1993, and several minor-league hockey teams. The 1960 NCAA Final Four was held here, culminating in Ohio State, led by Jerry Lucas and John Havlicek (with future coaching legend Bobby Knight as the 6th man) beating local heroes and defending National Champions California, led by Darrell Imhoff.

The Beatles played here on August 19, 1964 and August 31, 1965, and Elvis sang here on November 13, 1970 and November 28 & 29, 1976. It was the site of Neil Young’s 1978 concert that produced the live album

Live Rust and the concert film

Rust Never Sleeps, and the 1986 Conspiracy of Hope benefit with Joan Baez, Lou Reed, Sting and U2. The acoustics of the place, and the loss of such legendary venues as the Fillmore West and the Winterland Ballroom, make it the Bay Area’s holiest active rock and roll site. 2600 Geneva Avenue at Santos Street, in Daly City. 8X bus.

In addition to the preceding, Elvis sang at the Auditorium Arena (now the Kaiser Convention Center, near the Laney College campus in Oakland) early in his career, on June 3, 1956 and again on October 27, 1957; and the San Francisco Civic Auditorium (now the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium, 99 Grove Street at Polk Street) on October 26, 1957.

* SAP Center at San Jose. Formerly the San Jose Arena and the HP Pavilion, this building has hosted the NHL’s San Jose Sharks since 1993. The Warriors played here in 1996-97, while their Oakland arena was being renovated. If you’re a fan of the TV show

The West Wing, this was the convention center where the ticket of Matt Santos and Leo McGarry was nominated. 525 W. Santa Clara Street at Autumn Street, across from the Amtrak & CalTrain station.

* Avaya Stadium. The brand-new home of Major League Soccer's San Jose Earthquakes, it is soccer-specific and seats 18,000 people. 1123 Coleman Avenue & Newhall Drive; 41 miles from downtown Oakland, 46 from downtown San Francisco, 3 1/2 from downtown San Jose. ACE (Altamont Commuter Express) to Great America-Santa Clara.

This is actually the 3rd version of the San Jose Earthquakes. The 1st one played in the original North American Soccer League from 1974 to 1984, at Spartan Stadium. This has been home to San Jose State University sports since 1933, it hosted both the old Earthquakes, of the original North American Soccer League, from 1974 to 1984. It's hosted 3 games of the U.S. national team, most recently a 2007 loss to China. 1251 S. 10th Street, San Jose. San Jose Municipal Stadium, home of the Triple-A San Jose Giants, is a block away at 588 E. Alma Avenue. From either downtown San Francisco or downtown Oakland, take BART to Fremont terminal, then 181 bus to 2nd & Santa Clara, then 68 bus to Monterey & Alma.

The 2nd version of the Quakes played at Spartan Stadium from 1996 to 2005, but ran into financial trouble, and got moved to become the Houston Dynamo. The 3rd version was started in 2008, and until 2014 played at Buck Shaw Stadium, now called Stevens Stadium, in Santa Clara, on the campus of Santa Clara University. Also accessible by the Santa Clara ACE station.

* Stanford Stadium. This is the home field of Stanford University in Palo Alto, down the Peninsula from San Francisco. Originally built in 1921, it was home to many great quarterbacks, from early 49ers signal-caller Frankie Albert to 1971 Heisman winner Jim Plunkett to John Elway. It hosted Super Bowl XIX in 1985, won by the 49ers over the Miami Dolphins – 1 of only 2 Super Bowls that ended up having had a team that could have been called a home team. (The other was XIV, the Los Angeles Rams losing to the Pittsburgh Steelers at the Rose Bowl.)

It also hosted San Francisco’s games of the 1994 World Cup, and the soccer games of the 1984 Olympics, even though most of the events of those Olympics were down the coast in Los Angeles. It hosted 10 games by the U.S. national team, totaling 4 wins, 2 losses, 2 draws.

The original 85,000-seat structure was demolished and replaced with a new 50,000-seat stadium in 2006. Arboretum Road & Galvez Street. Caltrain to Palo Alto, 36 miles from downtown Oakland, 35 from downtown San Francisco, 19 from downtown San Jose.

* California Memorial Stadium. Home of Stanford’s arch-rivals, the University of California, at its main campus in Berkeley in the East Bay. (The school is generally known as “Cal” for sports, and “Berkeley” for most other purposes.) Its location in the Berkeley Hills makes it one of the nicest settings in college football. But it’s also, quite literally, on the Hayward Fault, a branch of the San Andreas Fault, so if “The Big One” had hit during a Cal home game, 72,000 people would have been screwed. With this in mind, the University renovated the stadium, making it safer and ready for 63,000 fans in 2012. So, like their arch-rivals Stanford, they now have a new stadium on the site of the old one.

The old stadium hosted 1 NFL game, and it was a very notable one: Due to a scheduling conflict with the A’s, the Raiders played a 1973 game there with the Miami Dolphins, and ended the Dolphins’ winning streak that included the entire 1972 season and Super Bowl VII. 76 Canyon Road, Berkeley. Downtown Berkeley stop on BART; 5 1/2 miles from downtown Oakland, 14 from downtown San Francisco, 48 from downtown San Jose.

Yankee Legend Joe DiMaggio, who grew up in San Francisco and later divided his time between there and South Florida, is buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Colma, on the Peninsula. 1500 Mission Road & Lawndale Blvd. BART to South San Francisco, then about a 1-mile walk.

The Fillmore Auditorium was at Fillmore Street and Geary Boulevard, and it still stands and hosts live music. Bus 38L. Winterland Ballroom, home of the final concerts of The Band (filmed as

The Last Waltz) and the Sex Pistols, was around the corner from the Fillmore at Post & Steiner Streets. And the legendary corner of Haight & Ashbury Streets can be reached via the 30 Bus, taking it to Haight and Masonic Avenue and walking 1 block west.

San Francisco, like New York, has a Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), at 151 3rd Street, downtown. The California Palace of the Legion of Honor is probably the city’s most famous museum, in Lincoln Park at the northwestern corner of the city, near the Presidio and the Golden Gate Bridge. (Any of you who are Trekkies, the Presidio is a now-closed military base that, in the Star Trek Universe, is the seat of Starfleet Command and Starfleet Academy.) And don’t forget to take a ride on one of them cable cars I’ve been hearing so dang much about.

Oakland isn’t much of a museum city, especially compared with San Francisco across the Bay. But the Oakland Museum of California (10th & Oak, Lake Merritt BART) and the Chabot Space & Science Center (10000 Skyline Blvd., not accessible by BART) may be worth a look.

The tallest building in Northern California is the iconic Transamerica Pyramid, 853 feet high, opening in 1972 at 600 Montgomery Street downtown. If all goes according to schedule, it will be superseded next year by the Salesforce Tower, also downtown, at 415 Mission Street, rising 1,070 feet. Another skyscraper will open around the same time in Los Angeles, slightly higher, so the Salesforce Tower won't be the tallest building in California, much less the American West.

While San Francisco has been the setting for lots of TV shows (from

Ironside and

The Streets of San Francisco in the 1970s, to

Full House and

Dharma & Greg in the 1990s), Oakland, being much less glamorous, has had only one that I know of:

Hangin' With Mr. Cooper, comedian Mark Curry's show about a former basketball player who returns to his old high school to teach.

In contrast, lots of movies have been shot in Oakland, including a pair of baseball-themed movies shot at the Coliseum:

Moneyball, based on Michael Lewis' book about the early 2000s A's, with Brad Pitt as general manager Billy Beane; and the 1994 remake of

Angels In the Outfield, filmed there because a recent earthquake had damaged the real-life Angels' Anaheim Stadium, and it couldn't be repaired in time for filming.

Movies set in San Francisco often take advantage of the city's topography, and include the

Dirty Harry series,

Bullitt (based on the same real-life cop, Dave Toschi);

The Maltese Falcon, starring Humphrey Bogart; Woody Allen's Bogart tribute,

Play It Again, Sam; The Lady from Shanghai, the original version of

D.O.A., Alfred Hitchcock's

Vertigo,

48 Hrs., and

Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home -- with the aircraft carrier USS Ranger, at the Alameda naval base, standing in for the carrier

Enterprise, which was then away at sea.

The 1936 film

San Francisco takes place around the earthquake and fire that devastated the city in 1906. And

Milk starred Sean Penn as Harvey Milk, America's 1st openly gay successful politician, elected to San Francisco's Board of Supervisors in 1977 before being assassinated with Mayor George Moscone the next year.

Movies set in San Francisco often have scenes filmed there and in Oakland, including

Pal Joey, Mahogany, Basic Instinct, the James Bond film

A View to a Kill, and

Mrs. Doubtfire, starring San Francisco native Robin Williams.

*

So, if you can afford it, go on out and join your fellow Giant or Jet fans in going coast-to-coast, and take on the legendary, but now-struggling San Francisco 49ers. After all, the Giants have won more NFL Championships, if not yet as many Super Bowls. The Jets? Well, their 1 is still more iconic than any of the Niners' 5.