April 8, 1974, 50 years ago: A testament to longevity, perseverance, strength of body and strength of character is finalized, as Hank Aaron becomes Major League Baseball's all-time home run leader.

Henry Louis Aaron was born on February 5, 1934 in Mobile, Alabama. Like Mickey Mantle, he had to play local semipro baseball because his high school did not have a baseball team. His timing was right: He was 13 years old when Jackie Robinson reintegrated what we would now call Major League Baseball, with the Brooklyn Dodgers. When he was 15, he got a tryout with the Dodgers, but did not get a pro contract. He remained with the Mobile Black Bears, earning $3.00 per game.

Also like Mantle, he began his professional career as a shortstop, but his fielding was such that he was switched to the outfield. In between, he was also tried at 2nd base. In 1952, he was signed by the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League. He was soon noticed by the New York Giants, who already had former Negro League stars Willie Mays and Monte Irvin; and the Boston Braves, who had integrated with 1948 National League Rookie of the Year Sam Jethroe.

"I had the Giants' contract in my hand," Aaron would later say, "but the Braves offered $50 a month more. That's the only thing that kept Willie Mays and me from being teammates: Fifty dollars." $50 in 1952, with inflation, is about $579 in 2024 money. On such hinge moments does the history of a sport sometimes hang in the balance. On June 12, 1952, the Braves paid the Clowns $10,000 for his contract.

For the 1953 season, the Braves moved to Milwaukee. He made their major league roster in 1954. He made his major league debut on April 13, at Crosley Field in Cincinnati. Wearing Number 5, batting 5th, and playing left field, he went 0-for-5. Eddie Mathews hit 2 home runs, but the Cincinnati Reds beat the Braves, 9-8. On April 23, at Busch Stadium (formerly Sportsman's Park) in St. Louis, he hit his 1st career home run, off former Yankee Vic Raschi, by then with the St. Louis Cardinals.

For the 1955 season, he switched to Number 44, and was moved to right field. Don Davidson, the Braves' public relations director, began listing him as "Hank" in official releases. From then on, "Henry" and "Hank" would be used interchangeably. He even had competing nicknames: "Bad Henry" (being bad for pitchers to face) and "Hammerin' Hank" (a nickname previously given to Detroit Tigers Hall-of-Famer Hank Greenberg).

In 1956, he won his 1st batting title with a .328 average, and the Braves finished just 1 game behind the Brooklyn Dodgers for the Pennant. In 1957, the Braves won their 1st Pennant since 1914. They clinched on September 23, with Aaron hitting a game-winning home run in the bottom of the 11th, off Billy Muffett of the Cardinals. Aaron was also named the NL's Most Valuable Player. It would be his only MVP award.

They faced the Yankees in the World Series. Hank later said that Yankee Stadium intimidated them, but that the Yankees did not. The Braves won the Series in 7 games, clinching at Yankee Stadium. They won the Pennant again in 1958, but lost the Series to the Yankees.

In 1959, Hank won another batting title, but the Braves finished in a tie for the Pennant with the Dodgers, who had moved to Los Angeles, and the Dodgers won the subsequent Playoff. As it turned out, that would be the closest Hank would get to another World Series.

The Gold Glove Award for fielding excellence was first given in 1958, and Hank won it for National League right fielders in each of its 1st 3 seasons. He would never win another, through no fault of his own, as Frank Robinson and Roberto Clemente would dominate that award.

In the Winter of 1960, Hank appeared on the TV show Home Run Derby. He was the show's most successful player, winning 6 games. With the show's prizes, including bonuses for consecutive homers, he won $13,500. He had been paid $35,000 the season before.

By this point, he was already regarded as one of the best all-around players in the game, along with Mantle and Mays. Most observers, including Home Run Derby host Mark Scott, took note of how he was then a bit skinny, but had "quick wrists." At that point, if you had told longtime baseball people that he would end up with over 3,000 hits, they probably would have believed it. If you had told them he would hit 500 home runs, they might have believed that.

But if you had told them that Hank Aaron would be the man to break Babe Ruth's career record of 714 home runs, that would have never occurred to them. Most people thought that, if it ever happened, it would be either Mantle or Mays who did it.

The Braves remained in contention in the early 1960s, but didn't win another Pennant. The novelty of Milwaukee being in the major leagues began to wear off. And the arrival of the Minnesota Twins in 1961 took the States of Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota, and even westernmost Wisconsin, out of what would now be called the Braves'"market." Attendance dropped, and team owner Bill Bartholomay moved them to Atlanta for the 1966 season.

Hank led the NL in homers and RBIs again in 1966. He led it in homers, slugging, runs and total bases in 1967. Moving from Milwaukee County Stadium to Atlanta Stadium helped his hitting: Atlanta had the highest elevation of any major league city until Denver got the Colorado Rockies in 1993, and the ball flew out of the stadium. It became known as "The Launching Pad."

On July 14, 1968, at Atlanta Stadium, against Mike McCormick of the San Francisco Giants, Hank hit the 500th home run of his career. He was only the 8th player to reach that milestone, following Babe Ruth, Jimmie Foxx, Mel Ott, Ted Williams, Mays, Mantle, and Mathews.

He was only 34 years old, showed no sign of slowing down, and was playing in a great hitter's park. Mantle was succumbing to his injuries, and would retire just before the next season, with 536 home runs. Mays had surpassed Mantle, and had also surpassed Ott (511) to become the NL's all-time home run leader. He had surpassed Williams (521) and Foxx (534). With Mantle having fallen away, the consensus was that, if any player would surpass Ruth's all-time record of 714, it was going to be Mays. Suddenly, baseball fans had to reckon with the possibility that it could be Aaron. He ended the season with 510.

In 1969, the Divisional Play Era began. The Braves and the Reds were put into the NL's Western Division, and the Cubs and the Cardinals into the Eastern Division, despite Atlanta and Cincinnati being further east than Chicago and St. Louis. The Braves won the Division, as Hank matched his uniform number with 44 home runs in a season for the 4th time, including his 537th, to pass Mantle; and again led the NL in total bases. But the Braves were swept by the New York Mets in the 1st-ever NL Championship Series. It would be Hank's last postseason appearance. He now had 554 home runs.

On May 17, 1970, at Crosley Field in Cincinnati, off Wayne Simpson, he singled home Félix Millán. It was his 3,000th career hit. It made him the 1st player to reach both 3,000 hits and 500 home runs, beating Mays to the dual distinction by 2 months. Also in that game, he hit a home run, and singled and scored the winning run in the 10th inning. He finished the season with 592 home runs.

In 1971, Hank tied Mathews' franchise record with 47 home runs, including the 600th of his career, on April 27, off Gaylord Perry of the Giants at Atlanta Stadium. He finished the season with 641. It wasn't enough to lead the NL, as Willie Stargell of the Pittsburgh Pirates hit 48. But it was a career high: For all the homers he hit, he never hit 50 in a season. And he only shared the team record, with Mathews, until Andruw Jones hit 51 in 2005.

In 1972, Hank surpassed Musial's record of 6,134 total bases, joined Ruth as the only players with 2,000 career RBIs, and, on June 11, hit the 649th home run of his career, surpassing Mays for 2nd all-time. Mays would retire the next season, with 660.

When the 1972 season ended, Henry, or Hank (he answered to both), had 673. He would turn 39 in the off-season, but, except for his ankle injury as a rookie, he had never been seriously hurt. It was no longer a question of, "Can he do it?" Only of, "When?" and "Will anything short of a career-ending injury stop him?"

In 1973, it looked like no pitcher could stop him. He just kept slugging away. As America dealt with the fallout from the end of its role in the Vietnam War, and the drip-drip-drip of revelations of the Watergate scandal then engulfing President Richard Nixon, the chase for the record was a welcome distraction for baseball fans. On July 21, at Atlanta Stadium, against Ken Brett of the Phillies (whose brother George would soon make his major league debut for the Kansas City Royals), Hank tallied Number 700.

The attention mounted. Soon, he was getting more mail than anybody in America, except Nixon himself. But, as with Nixon, some of it was hate mail. And some of it was terribly racist in nature. I won't quote any of it here. But at a time when civil rights legislation was an established fact of life, black people were leading the way in popular music, and black directors were making some of the most popular movies (including "blaxploitation films" like Shaft, Superfly, Blacula, Foxy Brown, Cleopatra Jones and Uptown Saturday Night), some people were furious that a black man was in position to break Ruth's record.

Even some people who didn't seem to be racist didn't want the record broken, saying that Hank getting to 715 would make people "forget" Ruth. "I don't want them to forget Babe Ruth," Hank said. "I just want them to remember me."

It didn't help that Ruth was dead. He would have been 66 years old when Roger Maris of the Yankees broke the single-season record of 60 with his "61 in '61." He had a very unhealthy lifestyle, but had he taken care of himself, it wouldn't have been impossible for him to still be alive at age 78 in 1973, and offer his support. His widow, Claire Ruth, didn't want either 60 or 714 to fall. But it's easy to imagine a still-living Bambino saying, on either occasion, "This is good for baseball. And anything that's good for baseball is good for me."

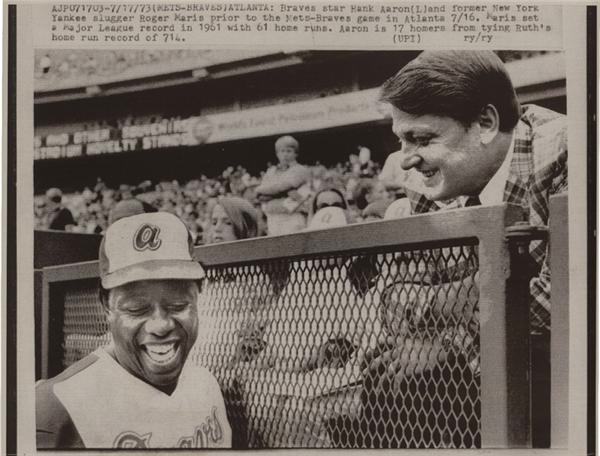

And with Jackie Robinson having died the preceding October, Maris, who got 100 men's shares of hate mail and phone calls, was the one man who had any idea of what Hank was going through. Now retired and running a beer distributorship in Gainesville, Florida, he made the 330-mile trip to Atlanta to meet Hank on July 16.

This photo is rare not just because it shows the two "home run kings" together,

but because it shows Roger Maris without his famous crew cut.

One thing Maris did not have to deal with in 1961 was racism. But he was mocked as "a .270 hitter." Aaron finished the 1973 season with a .301 average. Plagued by injuries, Maris retired in 1968, only 34 years old, with 275 home runs. Aaron was still going strong, in spite of the stress.

Hank realized he had another advantage. If Roger had fallen short, he would have had to start all over again the next year. If Hank fell short in 1973, he would still be able to break the record the next year. There was no pressure coming from the calendar. (It was coming from the haters.)

On September 29, the next-to-last day of the season, home to the Houston Astros, Hank hit Number 713 off Jerry Reuss. The Braves won, 7-0. On September 30, Hank had an RBI single in the 1st. He singled again in the 4th. He singled again in the 6th. Three hits, a successful game by almost anybody's standard. But now, it was almost impossible to break the record on this day. And he flew out in the 8th. The Astros won, 5-3.

The season was over, and Hank Aaron had 713 career home runs. And so began a long wait. And the threats kept coming in. There was even a mailed threat to kidnap his daughter at college. Hank hired a personal bodyguard, an Atlanta policeman named Calvin Wardlaw. He even stayed in a separate hotel from his teammates -- not because he wasn't allowed in the same hotel with his white teammates, as had been the case 20 years ago, but for his teammates' protection from anyone who might come after Hank.

On April 4, 1974, the Braves opened the new season against the Reds at Riverfront Stadium. In the top of the 1st inning, Hank drilled a pitch from Jack Billingham over the fence in left-center field. It was Number 714. When he got to 3rd base, he got a handshake from Pete Rose, who would have a similar moment on that field in 1985, when he officially surpassed Ty Cobb for most career hits. When Hank got to home plate, he received a handshake from Reds catcher Johnny Bench. Also on hand to offer his congratulations were Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and Vice President Gerald Ford -- but not Nixon.

April 8, 1974. Opening Night in Atlanta. The attendance was announced as 53,774, and it remains a home record for the Braves franchise, in any city. The game was broadcast live on NBC, just in case. The Braves were playing the Los Angeles Dodgers, who were wearing black armbands in memory of Bobbie McMullen, wife of Dodger 3rd baseman Ken McMullen. She had died of cancer 2 days earlier.

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn was not in attendance. Nor was Nixon, who was getting deeper and deeper into Watergate. But the Governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter, was there. So was the Mayor of Atlanta, the city's 1st black man so elected, Maynard Jackson. So was Pearl Bailey, who sang the National Anthem, as she had for the Mets' World Series clincher in 1969. So was Sammy Davis Jr.: The great song-and-dance man said he would pay $25,000 -- about $125,000 in today's money -- for the record-breaking home run ball.

Al Downing was the starting pitcher for the Dodgers. The lefthander from Trenton, New Jersey had been the 1st black pitcher for the Yankees, in 1961. In 1964, he had led the American League in strikeouts, the 1st black pitcher to have done that. He had worn Number 24 for the Yankees, the same number that Mays had made famous with the Giants. Now, with the Dodgers, he was wearing 44, the same number as Aaron.

Hank led off the bottom of the 2nd, and drew a walk. Dusty Baker doubled him home, to give the Braves a 1-0 lead. The Dodgers took a 3-1 lead in the top of the 3rd, and still held it in the bottom of the 4th. Darrell Evans reached 1st base on an error. That brought Hank to the plate.

Downing threw a curveball, and it went into the dirt for ball 1. At 9:07 PM Eastern Daylight Time, he threw a fastball.

Milo Hamilton had the call for WGST, 920 on the AM dial (now WGKA):

Henry Aaron, in the second inning, walked and scored. He's sittin' on 714. Here's the pitch by Downing. Swinging. There's a drive into left-center field! That ball is gonna be... outta here! It's gone! It's 715! There's a new home run champion of all time, and it's Henry Aaron! The fireworks are going! Henry Aaron is coming around third! His teammates are at home plate! And listen to this crowd! This sellout crowd is cheering Henry Aaron, the home run king of all time!"

Because of Hamilton's call, Aaron would spend the rest of his life being called "the Home Run King," much more often than "the home run leader."

The Dodgers' telecast, on KTTV-Channel 11, had Vin Scully with the call. Having broadcast for the team since 1950, when they were still in Brooklyn, and still had black MLB pioneers like Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe, he knew what the moment meant:

One ball and no strikes, Aaron waiting, the outfield deep to straightaway. Fastball, there's a high drive to deep left-center field! Buckner goes back, to the fence, it is gone!

Scully then paused, as Aaron got around the bases and reached home plate, then resumed:

What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the State of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world: A black man is getting a standing ovation, in the Deep South, for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.

It was a marvelous moment, and it was embraced by 99.99 percent of baseball fans. Writing about the event 30 years later, Tom Stanton would title his book about the record chase Hank Aaron and the Home Run That Changed America.

Bill Buckner was the Dodgers' left fielder that night. He climbed the fence to try to catch the ball, but he had no chance. After his error allowed the winning run to score in the Mets' Game 6 win over the Boston Red Sox in the 1986 World Series, someone suggested that, in concert with "The Curse of the Bambino" on the Red Sox, Ruth was punishing Buckner for not catching the ball. This was stupid: How did this person explain all the other outfielders who failed to catch Aaron's home run balls, and weren't "punished"? Or Downing, and the other pitchers who gave them up?

There was a scary moment. With all of the death threats, including from some men claiming they would be in attendance with rifles to shoot Hank before he could reach home plate (as if the home run wouldn't have counted anyway), bodyguard Wardlaw was looking around with binoculars for men with guns, like a Secret Service agent, and had his own gun ready.

After all, it had been 11 years since the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy and civil rights leader Medgar Evers; 9 years since that of Malcolm X; 8 years since The Beatles had gotten death threats on their last tour; 6 years since the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Senator/Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, and the shooting of painter Andy Warhol; 5 years since the murder of actress Sharon Tate and 3 of her friends; 4 years since an attempted assassination of Pope Paul VI; and 2 years since an attempted assassination of Governor George Wallace of Alabama during a Presidential campaign. People already knew that celebrities were not necessarily safe.

(There was also an attempt to assassinate Queen Elizabeth II of Britain in 1970, but this was not revealed until many years later. The year 1975 would see 2 failed attempts to assassinate new President Gerald Ford. Five years after that, former Beatle John Lennon would be shot and killed. Within 4 months of that, President Ronald Reagan would be shot and nearly killed.)

Wardlaw knew that Hank was still in danger. And Britt Gaston (on the left in the photo) and Cliff Courtenay, 2 long-haired 17-year-olds from Waycross, Georgia, ran onto the field, and patted Hank on the back. It happened quickly, and Wardlaw had to make a quick decision as to what do to. In 2005, he recalled:

People asked me afterward, "Where were you for the big moment, Calvin?" And I tell them that my instinct was, at that moment, that, even if I could have gotten out there, my man was not in danger. And I tell them something else: What if I had decided to shoot my two-barreled .38 at those two boys, if I thought he was in a life-threatening situation, and had hit Hank Aaron instead, on the night he hit No. 715?

Gaston and Courtenay were arrested for disorderly conduct and trespassing, but nothing worse than that. Gaston's father bailed them out of jail at 3:30 AM, paying $100 for each of them. The next morning, the charges were dropped.

Taking no chances, Estella Aaron wrapped her arms around her son right after he got to home plate, as if to say, "If you want to hurt my son, you'll have to go through me, first." Herbert Sr., and brothers Herbert Jr. and Tommie, were also there.

Gaston went on to run a graphics business in South Carolina, was a season-ticket holder for University of Georgia football, and died of cancer in 2012, at age 55. Courtenay is now 66 years old, and an optometrist in Valdosta. Both had become friends with Aaron.

The ball dropped in front of an ad for BankAmericard, whose name was changed to Visa in 1976. It landed in the Braves' bullpen, where it was caught by reliever Tom House. House left the bullpen, and presented Hank with the ball. It was not sold to Sammy Davis Jr. It now resides in the museum section of the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, as does the bat Hank hit it with, and so does the entire uniform that he wore that day.

Governor Carter gave him a Georgia license plate with his initials and the magic number: HLA 715. "Thank God it's over," Hank said.

Jimmy, Hank and Billye

Hank finished the season with 20 home runs at age 40, and 733 for his career. That remains a record for home runs for a single team. (Ruth hit 659 for the Yankees.)

In 1970, Bud Selig, a Milwaukee car dealer who had been trying to bring MLB back to his hometown after the Braves left, had bought the bankrupt Seattle Pilots, moved them to Milwaukee County Stadium, and given them the name of every pro baseball team in the city before the Braves: The Milwaukee Brewers. At the time, they were in the American League, which, unlike the National League, had adopted the designated hitter.

On November 2, 1974, recognizing that even he had slowed down -- he had been mainly a 1st baseman from 1971 onward, and was playing left field the night he hit Number 715 -- the Braves traded Hank Aaron back to his 1st major league city. He went to the Brewers, who sent the Braves outfielder Dave May, who had been an All-Star in 1973; and Roger Alexander, a pitcher then in Class AA, who ended up never making the major leagues.

Milwaukee fans welcomed Hank back with open arms. But it soon became clear that he was at the end of the line. In 1975, he batted .234 with just 10 home runs, giving him 745. He was still selected to the All-Star Game, held in Milwaukee. It was his 24th, tying a record held by Musial and Mays.

In 1976, he batted .229. On July 20, batting at County Stadium against Dick Drago of the California Angels, he hit his 755th career home run. Nobody knew it at the time, but, with more than 2 months left in the season, it would be his last.

On October 3, the Brewers closed the season at home against the Tigers. Hank was the DH, and batted in his customary 4th position, despite all evidence that he was done. He singled home Charlie Moore in the bottom of the 6th, and was replaced by pinch-runner Jim Gantner, to a standing ovation.

It was his 3,771st career hit, then 2nd all-time behind only Ty Cobb. In other words, he had over 3,000 hits that weren't home runs. He had 1,477 extra-base hits, still a record: 624 doubles and 98 triples, to go with his 755 home runs. It was his 2,297th run batted in, also still a record. It gave him 6,856 total bases, also still a record.

He also retired with these statistics: A .305 batting average, a .374 on-base percentage, a .555 slugging percentage, and a 155 OPS+. And he retired with another interesting distinction: He was the last former Negro League player who was still playing Major League Baseball.

In 1982, his 1st year of eligibility, he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. In 1999, The Sporting News named its 100 Greatest Baseball Players. Hank was ranked 5th, trailing Ruth, Mays, Cobb and Walter Johnson. In 2022, ESPN named its 100 Greatest Baseball Players. Hank actually rose, ranking 3rd behind Ruth and Mays.

When Turner Field opened for the 1997 season, its address was 755 Hank Aaron Drive. Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium (the name was changed in 1975) was torn down, to make way for parking for Turner Field, but the sign beyond the left field fence to mark where the record-breaking ball fell was restored to its former spot, on a fence.

In 2017, Turner Field was replaced by SunTrust Park, now named Truist Park, whose address is 755 Battery Avenue. Because the City of Atlanta didn't want to give up the Aaron statue outside Turner Field, a new statue of Hank was dedicated at Truist Park's Monument Garden. The Brewers also put up a statue of him at American Family Field, and both teams retired his Number 44.

In 1997, his hometown of Mobile opened the 6,000-seat Hank Aaron Stadium. Honoring him, but also a family of local activists, the address is 755 Bolling Brothers Boulevard. In 2002, President George W. Bush, a former owner of the Texas Rangers, gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

After his retirement, Aaron was hired by the Braves' front office. Even more so than as an active player, he fought for more inclusiveness in baseball.

On August 7, 2007, Barry Bonds of the San Francisco Giants stepped to the plate against Mike Bascik of the Washington Nationals, and hit his 756th career home run. Already having the single-season home run record, with 73 in 2001, he now held the career record as well. He would finish the season with 763, and retire.

I did not see Hank hit Number 715. Even though it was only 9:07 PM Eastern Time, my mother made me go to bed. And, at the age of 4, I wouldn't have been aware of it, anyway.

I did not see Barry hit Number 756. It was 11:46 PM Eastern Time, but, at that point in my life, staying up late wasn't an issue. Nor was access: The game was on ESPN. I chose not to watch it, because I knew that Bonds had cheated, using performance-enhancing drugs. Aaron was a better sport about it than I was. Although he didn't go to San Francisco for the game, he taped a message to be played on the video board at what's now named Oracle Park:

I would like to offer my congratulations to Barry Bonds on becoming baseball's career home run leader. It is a great accomplishment which required skill, longevity, and determination. Throughout the past century, the home run has held a special place in baseball, and I have been privileged to hold this record for 33 of those years.

I move over now and offer my best wishes to Barry and his family on this historical achievement. My hope today, as it was on that April evening in 1974, is that the achievement of this record will inspire others to chase their own dreams.

Bonds was now, and remains, and is likely to remain for a very long time, the all-time home run leader. But, for so many, Aaron was, and is, still the Home Run King. Including myself: Every time I look at a digital clock and see either 7:15 or 7:55, I think of Hank Aaron. Even though I wasn't old enough to have watched it, and have never lived anywhere near either Milwaukee or Atlanta.

Hank Aaron died in Atlanta on January 22, 2021, just short of his 87th birthday.