Along with the late Henri Richard of the Montreal Canadiens,

Bill Russell is the only North American professional athlete

with more championship rings than he has fingers.

April 30, 1956: The NBA Draft is held in New York. With the 1st pick, the Boston Celtics -- having just completed their 1st 10 seasons, and not yet having appeared in an NBA Finals -- select Tommy Heinsohn, forward from the nearby College of the Holy Cross.

With the 2nd pick, the Rochester Royals selected Sihugo Green, a guard from Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. Green was a decent player, but hardly the kind of star you would expect to go as the 2nd pick overall.

With the 3rd pick, the St. Louis Hawks draft Bill Russell, a center who had led the University of San Francisco to back-to-back National Championships. It looked like the Hawks had gotten the better player.

But later that day, the Hawks traded the rights to Russell to the Celtics, for center Ed Macauley and forward Cliff Hagan.

Result: Over the next 13 seasons, Russell would lead the Celtics to 12 NBA Finals, and 11 NBA Championships. The Celtics became the most dominant team in North American sports history -- not winning as many World Championships as Major League Baseball's New York Yankees or the National Hockey League's Montreal Canadiens, but winning more in a short period of time.

Meanwhile, the Hawks won just 1 title, and were forced to move out of St. Louis, to Atlanta, where they have been a perennial letdown.

It is the biggest transactional blunder in the NBA's 75-year history. How could the Hawks have been so dumb?

How dumb were they? Maybe not as dumb as we've been led to believe.

Top 5 Reasons You Can't Blame the St. Louis Hawks for Trading Bill Russell

5. Money. As the biggest star coming out of college basketball, Russell was already believed to be ready to demand big money, which most NBA team owners didn't have. Hawks owner Ben Kerner didn't have it. Celtics owner Walter Brown did, because he also owned his arena, the Boston Garden, and the other team that played there, the NHL's Boston Bruins.

What's more, Brown owned the Ice Capades. At the time, it was a bigger moneymaker than the NBA or the NHL. So was the Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus. It came to New York every April, and so the Madison Square Garden Corporation gave them choicer dates. This forced the Rangers in 1950, and the Knicks in 1951, to play Finals games on the road, possibly costing them titles.

4. The Rochester Royals. They had a chance to select Russell, but passed on him. Why? Because Brown made a deal with Royals owner Les Harrison: Select somebody other than Russell, and I'll add Rochester to the Ice Capades' tour. It was an offer Harrison couldn't refuse. (And no heads -- human, horse, or otherwise -- were hurt in the process.)

It was a short-term fix for the Royals. But that's the way the NBA had to operate at the time. A year later, Harrison moved the Royals to Cincinnati. They won the NBA Championship in 1951. In the 70 years since, this franchise, now known as the Sacramento Kings, has never been back to the NBA Finals. But Harrison did what he had to do to stay in business, and that meant giving up a chance at a man who could have become one of the NBA's greatest players ever, and did.

But he might not have:

3. The Big Man Theory. Until Michael Jordan led the Chicago Bulls to 6 NBA Championships -- 3 with Bill Cartwright at center, and 3 with Luc Longley -- it was generally believed that you had to have a big man in the middle to win an NBA Championship:

1949, '50, '52, '53 and '54 Minneapolis Lakers: George Mikan.

1957, '59, '60, '61, '62, '63, '64, '65, '66, '68 and '69 Boston Celtics: Bill Russell.

1958 St. Louis Hawks: Ed Macauley.

1967 Philadelphia 76ers, and 1972 Los Angeles Lakers: Wilt Chamberlain.

1970 and '73 New York Knicks: Willis Reed.

1971 Milwaukee Bucks, and 1980, '82, '85, '87 and '88 Los Angeles Lakers: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

1974 and '76 Boston Celtics: Dave Cowens.

1977 Portland Trail Blazers: Bill Walton.

1978 Washington Bullets: Elvin Hayes.

1979 Seattle SuperSonics: Jack Sikma.

1981, '84 and '86 Boston Celtics: Robert Parish.

1983 Philadelphia 76ers: Moses Malone.

1989 and '90 Detroit Pistons: Bill Laimbeer.

But did you notice? Until Russell, Mikan was the only big man who was able to lead a team to an NBA title. Until Russell, the NBA's best players had been smaller guys who were good outside shooters, guys like Joe Fulks (1947 Philadelphia Warriors), Buddy Jeannette (1948 Baltimore Bullets), Bob Davies (1951 Rochester Royals), Dolph Schayes (1955 Syracuse Nationals) and Paul Arizin and Tom Gola (1956 Philadelphia Warriors).

Before Russell, there were 3 truly great "big men" in college basetball. Mikan, from DePaul University in Chicago, was one. Another was Bob Kurland of Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State). He never played pro ball, instead taking a job with Phillips Petroleum, with a great benefits package, including playing for their "semipro" team. And the other was Clyde Lovellette of the University of Kansas. He had a good pro career, winning titles with the Lakers and later as Russell's backup on the Celtics. But he was never a pro star.

But there was no model for what kind of college stars would become pro stars. Like I said, the NBA was only 10 years old at this point. In hindsight, Mikan was the model. Russell admitted that Mikan was his idol. Mikan enjoyed being the progenitor of the NBA's big men.

But at the time, he was seen as a freak of nature, a happy accident that the Lakers had gotten their hands on. Big men were considered to be slow. Mikan was a good shooter and a strong rebounder, but he wasn't fast. Russell was fast. Chamberlain turned out to be even faster.

In 2021 at the NBA's 75th Anniversary, in 1996 at the 50th, in 1971 at the 25th, Russell seemed like the obvious player to both select and hang onto. In 1956, he wasn't the obvious pick to do that. Maybe he should have been, but he wasn't.

2. St. Louis. It's not just that the Hawks were far behind the Cardinals in terms of popularity in the city. It's that St. Louis was a racially segregated city, in Missouri, a racially segregated State. Cardinal stars like Bob Gibson and Curt Flood would chafe under the policies that segregation forced, until federal law broke it.

Russell -- who would eventually, very accurately, title his autobiography Memoirs of an Opinionated Man -- might not have adjusted so well, having been a boy in segregated Louisiana, and grown up in noticeably (but not completely) more racially liberal Oakland. He eventually had problems with race relations in Boston. In St. Louis, it might have been worse. As a result, he might not have won all those titles with the Hawks.

Anyway, it's not as if the Hawks blew it completely:

1. The Hawks Won a Championship. In 1957, the Celtics and Hawks each made the NBA Finals for the 1st time. It went to double overtime of Game 7 before the Celtics won it. In 1958, both teams made it back, and Russell hurt his ankle in Game 3, and was out the rest of the way. The Hawks, led by the men traded for the rights to Russell, Hagan and St. Louis native Macauley, as well as Hall-of-Fame forward Bob Pettit, won the title in 6 games.

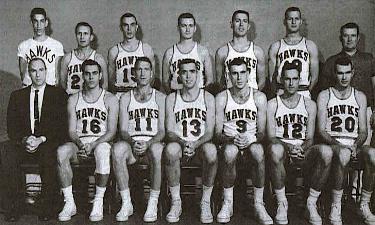

The 1958 NBA Champions.

Hagan is Number 16, Pettit 9, and Macauley 20.

In 1959, the Minneapolis Lakers won the Western Conference, and lost to the Celtics in the Finals. In 1960 and '61, the Hawks returned to the Finals, and lost to the Celtics both times. Still, at that point, the players the Hawks got for Russell had gotten them into 4 Finals, winning 1. It could have been better, but it was still better than anybody else except the Celtics were doing.

VERDICT: Guilty. In St. Louis and Atlanta (where they moved in 1968), the Hawks haven't won a title since 1958, or reached the Finals since 1961. And if Bob Gibson could play in St. Louis and win the fans over, Bill Russell could do it, too.

Usually, these Top 5 Reasons posts end with an acquittal. This one simply can't. None of the 5 reasons provides reasonable doubt. The Hawks might not have traded 17 NBA Championships overall, or the 11 that Russell won, for the 1 that they did win and the inability to stay put long-term. But they did make this trade.

That's how dumb they were.