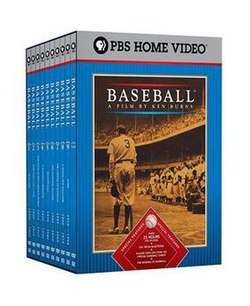

MLB Network just re-ran Ken Burns' Baseball miniseries. First running on PBS from September 18 to 28, 1994, just after Commissioner Bud Selig canceled the rest of the season, including the postseason, it was a godsend for disillusioned fans from The Bronx to Candlestick.

There's only so much you can cram into 9 "innings" of nearly 2 hours each. Some things he could, and should, have mentioned didn't get into the narrative.

Here's 10 things that he should have mentioned, but didn't, going, roughly, in chronological order. I'm not going to include The Tenth Inning, which had to go through 1994 to 2010 quickly.

1. The big names of the Amateur Era, 1845-68. Burns mentions the name of Alexander Cartwright, who comes closer than anyone else to being "the inventor of baseball." And he mentions the names of the brothers Harry and George Wright, the leading names of the 1st openly professional team, the 1869-70 Cincinnati Red Stockings.

But what about the great players in between? No mention of Jim Creighton, the 1st great pitcher, who died as the result of an in-game injury in 1862. No mention of Joe Start, probably the best hitter of that time. No mention of Lipman "Lip" Pike, the 1st Jewish man known to have played baseball at that level, and one of the best players of that era.

Start and Pike played into the professional era, and were teammates on the Brooklyn Atlantics team that ended the Red Stockings' unbeaten run in 1870. That game was mentioned, but none of the names of the players on that team were.

In The Tenth Inning, in connection with recent cheating, Burns finally mentioned Creighton: By snapping his wrist in an 1859 game between his Star Club and the Niagaras, both of Brooklyn, Creighton, then only 18 years old, could make his pitch go faster, inventing the fastball. At the time, it was seen as unfair. So it only took Burns 16 years to mention him -- for Creighton, 151 years. Burns had mentioned William "Candy" Cummings and his claim to have invented the curveball in 1867, a claim now considered dubious. But not Creighton, at least not the first time.

2. Chicago baseball in general, after the Black Sox Scandal of 1919-21. Chicago teams are mentioned only in passing: The Cubs as opponents of the Philadelphia Athletics in the 1929 World Series, as opponents of the Yankees in the 1932 World Series, and as opponents of the Mets in the 1969 National League Eastern Division Pennant race; while the White Sox are mentioned as being 1 of the 4 teams being in the 1967 American League Pennant race that went down to the last weekend of the season.

Luke Appling of the White Sox got mentioned. So did Ernie Banks of the Cubs. But except for 3 seconds of the 1959 World Series, at the beginning of Eighth Inning: A Whole New Ballgame, there is no footage of the White Sox after the Black Sox Scandal. Some very nice shots of Comiskey Park, and the heartbreaking shots of its demolition.

But there is no discussion of the 1959 Pennant-winning "Go-Go White Sox." No mention of Luis Aparicio and Nellie Fox from that team. No mention of Dick Allen (more about him in a moment). No mention of the 1977 "South Side Hit Men" or the 1983 AL Western Division title. Nor any mention of how the Cubs used "Superstation" WGN to become a team with a national following with their NL East title in 1984, followed by their shocking Playoff loss.

Narrator John Chancellor, reading the words written by Burns (or Geoffrey C. Ward), mentions that Carlton Fisk was not given a new contract by the Boston Red Sox after the 1980 season, and that he had signed with the White Sox. But only a photograph is shown: No game action for him in a White Sox uniform.

Burns said that Bill Veeck is best remembered for how he ran the St. Louis Browns from 1951 to 1953. This is not true: He is much better known for his 2 tenures as White Sox owner, 1959-61 and 1975-80. And had Veeck himself lived to be interviewed for the miniseries (he died in 1986), I'm sure he would rather have talked about what he did in Chicago -- including in his earliest executive job in baseball, working for the Cubs. He's the man who planted the ivy on the outfield wall at Wrigley Field, and led the construction of that ballpark's also-iconic scoreboard.

I realize that, from 1945 until the miniseries aired in 1994, only 1 Pennant was won by a Chicago team, the '59 Sox. But Burns could have said more.

For The Tenth Inning, which first aired 6 years before the Cubs ended their even longer drought at 108 years, Burns covered the Steve Bartman Game in the 2003 Playoffs, but spent much less time on that than he did on the Aaron Boone Game that took place the next night. Even then, he spent more time on his beloved BoSox than on the even-more-aggrieved Cubbies.

Also in The Tenth Inning, Burns showed only the last play of the 2005 World Series, ending an 88-year drought for the White Sox. That's 2 years longer than the Red Sox, on whose 2004 win he spent a couple of weeks, longer than it took for them to go from 3 outs from getting swept in the ALCS to sweeping the World Series, or so it seemed.

He also covered the 1998 home run record chase between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa. But, even then, it was about the men, not their teams. Not Sosa's Cubs, and not McGwire's Cardinals.

Which leads us to...

3. The St. Louis Cardinals. Burns covered Curt Flood in great detail, and Bob Gibson and his roles in the 1967 and '68 World Series in some detail as well. But he shortchanged the Cardinal team that won 4 Pennants and 3 World Series in 5 years from 1942 to 1946; and the Cardinal team that won 3 Pennants but just 1 World Series in 6 years from 1982 to 1987, he didn't mention at all.

Burns made far more of Ted Williams than he did of Ted's National League counterpart Stan Musial. He discussed Pete Gray, the one-armed outfielder for the 1945 St. Louis Browns, more than he did the Cardinals of that period. Indeed, when he discussed the 1946 World Series, it was almost as if the Cards were merely the opposition to the Red Sox. This would be repeated when he got to the 1986 World Series.

At the time of filming, Musial, Gibson, Enos Salughter, and many other major Cardinal figures were still alive. The only one he interviewed was Flood. He interviewed Bob Costas, who had broadcast for the Cardinals; but not former Cardinal broadcasters Harry Caray and Jack Buck, both still alive at the time. He included calls of Caray's and Buck's, but not interviews of either.

For a while now, we've heard the Cardinal publicity machine push St. Louis as "the best baseball town in America." Burns didn't mention that in his '94 miniseries. In The Tenth Inning, the expression was mentioned.

4. The "Mexican Jumping Beans." For all his discussion of the struggle between players and team management, Burns did not make a single mention of the Mexican League's 1946 overtures to major league players of more money and more control over their own fortunes. He cited Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo raiding the Negro Leagues for players for his country's league in 1937, but not the Mexican Jumping Beans.

Among the players who "jumped" to the Mexican League to take advantage of this, but later returned and were accepted back into the majors were New York Giants pitcher Sal Maglie and early Puerto Rican star Luis Olmo.

Given Burns' fetish for the battle over the reserve clause, and his mentions of the U.S. Supreme Court (upholding baseball's antitrust exemption in 1922 and the reserve clause against Flood in 1972), it is a surprise that he didn't mention the case that former Giants outfielder Danny Gardella brought against the baseball establishment, challenging the clause. Gardella won a round in federal court. Afraid that the whole thing would come tumbling down, Commissioner Albert "Happy" Chandler offered amnesty to the Jumping Beans if Gardella would drop his case. He did.

Burns interviewed Chandler, but all he showed of that interview was a brief clip of him singing "Take Me Out to the Ball Game." No mention of the Jumping Beans, or of Chandler's role in allowing the reintegration of the game. Gardella was also still alive at the time. So was Maglie. So was Olmo. None of them were interviewed.

Chandler (1898-1991) was 1 of 2 people that Burns interviewed who was born before 1900, along with former pitcher and Babe Ruth teammate Milt Gaston (1896-1996); and 1 of 7 who died before the series' premiere on September 18, 1994. The others were Ruth's sister Mamie Moberly (1900-1992), Ruth's teammate and longtime California Angels coach Jimmie Reese (1901-1994), broadcasting legend Red Barber (1908-1992), Cubs and Dodgers Hall of Fame 2nd baseman Billy Herman (1909-1992), All-American Girls Professional Baseball League player Dottie Green (1921-1992), and tennis legend and civil rights activist Arthur Ashe (1943-1993).

5. The Philadelphia Phillies. No mention of their 1950 Pennant-winners, the "Whiz Kids" -- not even of the fact that they were the last all-white team to win the NL Pennant. (The 1953 Yankees were the last all-white team to win a World Series.) No mention of their 1964 "Phillie Phlop." No mention of the aftermath of that, including how Richie -- make that "Dick" -- Allen was treated.

No mention of "Black Friday" in the 1977 Playoffs. The only mention of their 1980 World Series win, finally finishing atop the baseball world for the 1st team in their 98th season, was in connection with the section on free agency, talking about how Pete Rose had left his hometown team, the Cincinnati Reds, for the Phils. No mention of Mike Schmidt, who was possibly all of these things: The best all-around player of his generation, the best 3rd baseman ever, and the best player ever to wear the uniform of a Philadelphia baseball team.

I can excuse Burns for not including the 1993 World Series, in which the Toronto Blue Jays broke Philly fans' hearts with that 15-14 comeback in Game 4 and the Joe Carter walkoff homer in Game 6. It was close to production time.

But there were so many stories of the Fightin' Phils, their successes and their failures. Are they truly that much less interesting, historically, than the Red Sox? Or even the Cubs, who got slightly more mention?

6. The Milwaukee Braves. Burns mentioned in passing that the Boston Braves had moved to Milwaukee and set attendance records. And he showed Hank Aaron's walkoff home run that clinched the 1957 National League Pennant.

But nothing about how the Braves lifted up the previously untapped market of Milwaukee. And nothing about how the specific development of the Braves having built a new stadium, on the edge of the city where it had begun to shift to suburbs, and with over 10,000 parking spaces, directly doomed Ebbets Field and, eventually, the Dodgers as a Brooklyn team.

And how it also doomed other teams, to varying degrees: The New York Giants, the St. Louis Browns, the Washington Senators, and the Athletics first in Philadelphia, then in Kansas City. And it almost doomed other teams with small, tucked-away ballparks, and led to the building of multipurpose stadiums that doomed those ballparks: Sportsman's Park in St. Louis, Crosley Field in Cincinnati, Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, and Connie Mack Stadium in Philadelphia. I could add Comiskey Park in Chicago and Tiger Stadium in Detroit, but both were replaced by baseball-only stadiums.

7. The rise of Hispanic players. Armando Marsans and Rafael Almeida, white Cubans and the 1st 2 Hispanic players in MLB (they debuted together, with the 1911 Reds), weren't mentioned at all. Nor was Adolfo "Dolf" Luque, another white Cuban who was a great pitcher in the 1920s. Nor was Orestes "Minnie" Miñoso, the 1st black Hispanic player.

Orlando Cepeda, Juan Marichal, and the Alou brothers -- Felipe, Mateo (a.k.a. Matty) and Jesus -- of the early 1960s Giants, were barely mentioned. Their struggle with manager Alvin Dark, which helped hold a team with 5 Hall-of-Famers (Cepeda, Marichal, Willie Mays, Willie McCovey and Gaylord Perry) to just 1 Pennant and 4 other near-misses between 1959 and 1966, was not mentioned.

Burns went in-depth on Roberto Clemente, baseball's 1st Hispanic superstar. But he didn't mention Mexican pitching legend Fernando Valenzuela at all until The Tenth Inning. Nor did he mention Dennis Martinez, the Nicaraguan who pitched a perfect game and was a member of 2 Pennant winners. Nor did he mention Pedro Guerrero, the Dominican slugger who shared the World Series MVP with Ron Cey and Steve Yeager on the 1981 Dodgers.

He mentioned how the 1992 Toronto Blue Jays became the 1st team managed by a black man to win a World Series (though not that they were the 1st to even win a Pennant), but didn't mention any of their individual players, including their Hall of Fame Puerto Rican 2nd baseman Roberto Alomar and their Dominican ace Juan Guzmán.

(After 1994, which Burns couldn't have foreseen, Martinez played on a 3rd Pennant winner, and surpassed Marichal as the all-time winningest pitcher among Hispanics.)

Burns then overcompensated during his Tenth Inning. On the subject of Dominican prospects, and what was likely to happen to them when they tried to make it, including what happened to them when they didn't, he went into detail nearly as poignant as when he told of the racist barriers the Negro Leaguers and the early black major leaguers faced.

He interviewed 2 Dominican pitchers for the Dodgers' Gulf Coast League team in 2005: Gary Paris and Ramon Paredes. Both of them, 18 and 20 years old, respectively, spoke of how wonderful it would be if they made it. Neither did: Both were out of professional baseball by the close of the 2007 season. To add insult to injury, however unintentionally, in the graphics used to identify him, Burns misspelled Gary's name as "Gary Parris."

8. The players' revolt over Bobby Kennedy. When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, baseball was out of season. But the National Football League, already beginning its approach to becoming (apparently) more popular than baseball, was 48 hours from a new round of games, and Commissioner Pete Rozelle had to make a quick decision on whether to let the games go on. He did, and was ripped for it by the press and the public. The American Football League postponed its games for that Sunday, pushing them back to the week after the last regularly-scheduled slate of games.

Burns mentioned the myth that, after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King on April 4, 1968, baseball games were postponed out of respect to his memory, or to keep people out of harm's way during the rioting. According to Joe Distelheim in The Hardball Times:

A few teams had postponed their April 8 home openers, but when the Houston Astros decided to go ahead with their game against Pittsburgh, the Pirates, led by Roberto Clemente, Donn Clendenon, and their nine other black players, refused to play. They also said they wouldn’t take part in their next scheduled game against the Astros because it was April 9, the day of King’s funeral.

In St. Louis, some Cardinals players had gathered in the apartment of first baseman Orlando Cepeda and decided to tell Cardinals management they wouldn’t open the season as scheduled either. The Dodgers said they’d go ahead with their home opener against Philadelphia, but Phillies general manager John Quinn said his team would forfeit rather than play.

In the end, conflict was avoided. No games were played until April 10.

That would not be the case 2 months later, when Senator Robert F. Kennedy was shot on June 5, and died the next day. Some players didn't want to play on the day of the funeral, June 8. Some of the black players, appreciative of RFK's record in civil rights and his efforts to reach out to black voters, got some of the white players to stand with them, and appeal to their managers, in the hopes that the manager would appeal to the team's owner.

Some teams agreed to postpone their games, and make the next day a doubleheader. Some teams agreed to move their day games to night games. Some teams refused to do either. The objecting players refused to play, and most of those were fined.

Burns mentioned none of this. Indeed, in his introduction to Eighth Inning: A Whole New Ballgame, he (through Chancellor) said, "Americans lost a President, and a prophet.""The prophet" was Dr. King. But Bobby wasn't mentioned then, or at all.

9. The 1964 Pennant races and all they entailed. The Phillie Phlop, Dick Allen, and the repercussions. The Reds, and the fatal illness of their manager Fred Hutchinson. The rise of the Cardinals, although that was touched upon when he discussed 1967. The end of the Yankee Dynasty.

10. Jim Bouton and his book Ball Four."I'm 30 years old, and I have these dreams." With those words, Jim Bouton, once a star pitcher on the Yankees but now a marginal major leaguer due to injury and a reputation as an oddball, began his diary of the 1969 baseball season, which would be published in book form the next year, with the title of Ball Four: My Life and Hard Times Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues.

Nobody, not even Jim himself, had any idea of the impact that this book would have. The fact that the team's operation was so ridiculous, that they only existed for that 1 season, and that the current Seattle team, debuting in 1977, is named the Mariners, not the Pilots, makes

Ball Four seem like a novel, like the Pilots never actually existed. But they did. In a 2000 interview with baseball historian Rob Neyer for ESPN.com, Jim, unaware of my assessment, backed it up:

The Pilots existed for only one year. It's almost a magical story. They're like "Brigadoon." It's a Major League Baseball team that, in many respects, exists only within the pages of a book. It's like a fictional baseball team, so the characters in the book have almost become like fictional characters.

And they were perfect for the book. It was gold. Everyone one of those players was an interesting story, in one way or another. You had rookies, and you had grizzled veterans...

It was a perfect cast of characters, almost as if somebody had said, "This team's not going to win any games, but if someone writes a book, this'll be a great ballclub."

Bouton testified in Curt Flood's trial by reading passages from Ball Four. But Burns didn't mention that. Bouton left baseball at the height of the 1970 controversy to become a sportscaster, but made a comeback, and returned to the major leagues at age 39, as a September callup with the 1978 Atlanta Braves, even winning a game. But Burns didn't mention that, either.

Bouton closed the book with these words, which would have fit in very nicely with Ken Burns' text: "You spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time."

Honorable Mention. Nolan Ryan. 27 seasons. 324 wins. A record 5,714 strikeouts for his career. Seasons of 383 and 367 strikeouts, 1st and 3rd best all-time. A record 7 no-hitters, including pitching them at the record age of 43, then 44. Four postseason appearances with 3 teams. How much screen time did he get? 24 seconds in Eighth Inning: A Whole New Ballgame, and 44 seconds in Ninth Inning: Home, in the section on free agency. Total: 1 minute and 8 seconds -- or, roughly, 1 second for every 84 strikeouts.

Honorable Mention. Rickey Henderson. 25 seasons. 3,055 hits. 1,406 stolen bases in a career, including 130 in a season, both records. 2,295 runs scored, also a record. Bill James has said that if you split his career in 2, you'd have 2 Hall-of-Famers. And his personality, in all his complexity, makes him an even better story. How much mention did he get? None at all! There was a 3-second clip of him at the opening of The Tenth Inning. But his name wasn't mentioned.

Okay, so what should he have cut out, or at least cut down, to make room? The section on Ty Cobb's last years. Just as he breezed through discussion of what happened to Shoeless Joe Jackson in the 30 years between his last game and his death, he could have done the same for the 33 years between Cobb's last game and his death.

He also could have cited Lawrence S. Ritter's book The Glory of Their Times: Not only did that book help to jump-start the baseball nostalgia movement, but Ritter specifically said that he looked up players from the early 20th Century because Cobb's death got him to thinking of that era.

One thing I never noticed the first time around was that song that was played over the footage of Cobb's funeral was "Amazing Grace."

Spending as much time as he did on Curt Flood wasn't necessary. Yes, his thoughts on baseball's piece-by-piece integration were valuable. But half as much time on his lawsuit would have been fine.

And too much has been made about the Kirk Gibson home run. Let's face it: It wasn't even the 1st time Gibson had been a World Series hero. He did it for Detroit in 1984. The discussion of the Bill Buckner Game could have been cut a little, too.

And while we're (sort of) on the subject of the Red Sox: Why spend so much time on Fenway Park, when the old Yankee Stadium, Wrigley Field, and Comiskey Park and Tiger Stadium were also then still standing? (Wrigley still is.) There were some great shots of Comiskey, with others talking over it, but not much discussion of the ballpark.

Even with the amount of material that Ken Burns covered, there could have been more.