"I'm 30 years old, and I have these dreams." With those words, Jim Bouton began his diary of the 1969 baseball season, which would be published in book form the next year, with the title of Ball Four: My Life and Hard Times Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues.

Nobody had any idea of the impact that this book would have. It's almost as if the Major League Baseball pitching career that he had already had was becoming secondary. But then, as much as he loved baseball, Bouton was not all about it. He understood that it is often a microcosm of life, but it is not life and death.

James Alan Bouton was born on March 8, 1939, in Newark, New Jersey, and grew up in nearby Rochelle Park and Ridgewood, Bergen County. Jim and his brother Pete grew up as fans of the New York Giants baseball team. But when they were teenagers, the family moved from the suburbs of New York to the suburbs of Chicago, to Homewood, Illinois.

At this point, they would only get to see their heroes when they came to Wrigley Field to play the Chicago Cubs. On one such occasion, doing something that kids had been doing since the invention of dugouts, Pete held Jim by the legs, and he hung himself upside down over the visiting team dugout, pen in one hand, game program in the other, hoping to get an autograph from one of the Giants players.

He saw Alvin Dark, their shortstop and team captain, and said, "Hey, Al, my name's Jim, I'm not a Cub fan, I'm a Giant fan, I'm from New Jersey, can you sign my program, please?" After a minute, Pete pulled Jim back up, saw that he didn't get an autograph, and asked him what happened. Jim said Dark told him, "Take a hike, son."

Pete wasn't furious that a player had so coldly dismissed his brother. He was thrilled that a real live major league ballplayer had spoken to his brother: "No kidding? Alvin Dark told you to take a hike?"

When they got home, their mother asked them what happened. Rather than tell her who won, or about anything that happened in the actual game, Pete said, "Alvin Dark told Jim to take a hike!" After that, whenever someone in the Bouton family wanted to get rid of somebody, even if it was one of the parents, it would be, "Take a hike, Jim,""Take a hike, Mom," or, "Take a hike, Dad."

Jim was not a star pitcher in high school, hardly getting into a game, but always warming up for it, to the point where he was nicknamed "Warmup Bouton." It was a foreshadowing of the problem he would later face, as told in the pages of Ball Four. But in Summer leagues, he became a star, and got a baseball scholarship to Western Michigan University, in Kalamazoo. He was signed by the New York Yankees for $30,000.

When he reached the major leagues, he was given uniform Number 56, a very high number for the time. Later that season, clubhouse manager Pete Sheehy said he could now receive a smaller number, recommending 29. Jim said that he would rather keep 56, to remind him of just how difficult it is to stay in the major leagues.

He made his major league debut on April 22, 1962, at Yankee Stadium, pitching 3 innings in relief, without allowing a run. It didn't matter much, as the Yankees lost to the Cleveland Indians, 7-5. His next appearance was on May 6, in the 2nd game of a doubleheader against the Washington Senators. He went the distance, allowing 7 runs and 7 walks, but pitched a shutout in an 8-0 Yankee victory. After the game, he noticed a path of warm white towels from the clubhouse door to his locker. They were put there by Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford. Jim knew he had arrived.

Jim went 7-7 that year. The Yankees won the World Series, and he got a ring, but he did not appear in the Series. In 1963, just 24 years old, he went 21-7 with a 2.53 ERA, and made the All-Star Game for what turned out to be the only time. His fastball and gruff demeanor on the mound earned him the alliterative nickname "Bulldog" Bouton. Fans also loved that his unusual pitching motion caused his hat to frequently fly off his head.

He started Game 3 of the 1963 World Series, and pitched well, but Don Drysdale pitched better, and the Los Angeles Dodgers beat the Yankees 1-0, en route to a 4-game sweep. In 1964, he went 18-13, helping the Yankees win a tight Pennant race, and won Games 3 and 6 of the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, but the Yankees lost Game 7.

As Spring Training 1965 began, Jim was about to turn 26, and had good fastball, legendary teammates, and a career record of 46-27. But he hurt his elbow that year, one of many injuries that seemed to strike the old Yankee Dynasty at once. The Yankees finished 6th, and, for reasons that were almost entirely not his fault, Jim went 4-15.

That was when the nastier side of the old Yankees reared its head. When Jim was winning, his class clown antics got him labeled "colorful." His teammates didn't mind his intellectualism, his lefty politics, his outspokenness, or his impersonation of comedian Frank Fontaine in his "Crazy Guggenheim" role on The Jackie Gleason Show. But when he was losing, they acted like they didn't want to know him.

In Spring Training 1967, Jim was told, "You're having a better spring than Dooley Womack." Not wanting to rock the boat, he didn't say what he wanted to say, which was, "The Dooley Womack? I'm having a better spring than Whitey Ford or Mel Stottlemyre!" But he didn't have a good regular season. His fastball gone, he began experimenting with a knuckleball.

By 1968, the Dynasty was dead. On June 15, the Seattle Pilots, an expansion team that was going to begin play the next season, bought him from the Yankees, and assigned him to their top farm team, so that he could get work. As Spring Training came in 1969, he was about to turn 30, and he didn't know if he had enough left to make even a brand-new expansion team.

*

Another way that Jim was different was that he was friends with Leonard Shecter of the New York Post. Most Yankees hated him, because he was critical of them. Shecter was one of the "Chipmunks," the new breed of sportswriter who wasn't willing to accept the "Gee whiz, aren't these ballplayers all nice guys, virtuous guys who are good to kids, faithful to their wives, don't drink anything stronger than milkshakes, and only have pro-America and pro-God opinions" myth. Shecter thought that keeping the truth to yourself was not always a good idea.

The Yankees told Jim, "Don't talk to the reporters, especially that fuckin' Shecter." Jim wrote, "I heard 'fuckin' Shecter' so many times, I began to think that was his full name." But they became friends, and talked about the ballplayer image.

They agreed that most books "written by ballplayers" (always dictated to a sportswriter, who would arrange it so that it only made the player look good) were sappy, sanitized stories about the big names, and that it would be more interesting if a marginal player wrote a book about just how hard it was to make a living in baseball.

This was not a new idea: Jim Brosnan, a decent but not great pitcher, kept a diary in 1959, a season which saw him get traded from the Cardinals to the Cincinnati Reds. It was published as The Long Season, and got praise from some sources, and disdain from the baseball establishment, which presaged what Bouton would later go through. In 1961, Brosnan tried again, and was lucky that the Reds won the Pennant. That book was titled Pennant Race.

So there was precedent. Jim began writing notes at the Pilots' training camp in Tucson, Arizona. Just as he started writing, 2 things happened that would shape public perception of the book. One was that he negotiated his contract for the season, at a time when players were bound by baseball's reserve clause, which essentially bound them to a team for life, unless traded or released. He used the opportunity to describe his struggles to get what he thought he was worth from the Yankees.

The other big thing that happened was that Mickey Mantle retired, after 18 years of heroics and injuries. Jim told about how well Mickey had treated him. He also told about how Mickey could be juvenile and drunk, and not nice to young autograph seekers. (I wonder if he ever told any of them to "Take a hike, son.")

He also told about a combination of these phenomenons, Mickey leading Jim and some other young players onto the roof of the hotel they stayed at when they were playing the Washington Senators, an establishment now known as the Omni Shoreham. Because of the building's layout, the roof made it easy to be a Peeping Tom, watching women get dressed and undressed. Jim said the baseball term for this activity was "beaver shooting."

*

Jim made the team, but had 1 bad outing for the Pilots in April, and was sent down to the Vancouver Mounties of the Pacific Coast League. He was quickly brought back, but not used well. He began to see that he was never brought in during close games, only when the game was already out of hand, either way.

He began to suspect that manager Joe Schultz, pitching coach Sal Maglie, and general manager Marvin Milkes didn't trust him, because he was an oddball throwing an oddball pitch (the knuckleball -- not the screwball).

Maglie had a case: He was once not just a great pitcher, with one of the best curveballs of his time, but a former New York Giant, and one of Jim's heroes. But Milkes was out of his depth as a baseball executive. And Schultz should have understood marginal players better, as he was one, a backup catcher in the 1940s, although he did help the St. Louis Browns win their only Pennant in 1944.

He was a coach on the Cardinals' 1960s Pennant winners, but he seemed to forget that he was no longer working for Cardinals owner and beer baron Gussie Busch. He was always telling his players, "Zitz 'em, and go pound some Budweiser!" He was a company man to the end.

Jim would plead his case for more appearances, even starts, and Joe would nod, munch on a liverwurst sandwich, and tell Jim what he wanted to hear, and then not do it. Schultz was fired after that season, and remained a coach in the majors through 1976, but never managed again except on an interim basis with the 1973 Detroit Tigers. (Jim said that Joe had 2 favorite words: "Shitfuck" and "Fuckshit.")

"Establishment" players on the Pilots, like shortstop Ray Oyler and pitcher Fred Talbot (a former Yankee teammate) tended to stay away from him. Other oddballs, like pitcher Mike Marshall and outfielder Steve Hovley, gravitated toward him.

Jim told a story about being invited to his former high school's sports awards banquet. He took questions. A kid stood up, and asked Jim what he thought about long hair. Jim said the problem wasn't that an entire generation of teenage boys decided to let their hair get longer, it was that schools were ready to expel otherwise well-behaved kids over it. The kids gave him a standing ovation. The parents, he said, resolved never to invite Jim Bouton again.

Jim wrote about silly pranks (such as convincing Talbot he'd won $5,000, and hitting another pitcher with a fake paternity suit), and juvenile activity (pitcher Marty Pattin doing an impression of Donald Duck giving pitching advice, Pattin doing Donald Duck having an orgasm, catcher Greg Goossen seeing a plaque on a building saying, "Erected in 1929," and saying, "That's quite an erection").

He mentioned drinking. Lots of lots of drinking. Including by Mantle, but also by the Pilots players. When Schultz told the team to report for a game at 10:30 AM, catcher Jim Pagliaroni said, "Ten-thirty? I'm not even done throwing up at that hour."

He mentioned amphetamine use, beginning a paragraph with, "How fabulous are greenies? The answer is very." He said that some players couldn't function without them. He said that they helped his performance maybe 5 percent, which wasn't enough. He told of a normally mild-mannered player who took a called 3rd strike, and then lit into the umpire. When the player returned to the dugout, he was asked, "What happened?" and he said, "My greenie kicked in." Jim told of another player, normally not a power hitter, who was jacking the ball out in batting practice. Someone asked, "What got into him?" And another player said, "Four greenies."

He mentioned a story that outfielder Jim Gosger told about hiding in the closet (with, apparently, no irony) while his roommate fooled around with a local groupie (they were called "baseball Annies"), who said she'd never done it that way before. Jim stuck his head out of the closet, and said, "Yeah, surrre!" (Jim wrote it with 3 R's.) From that point onward, it became a catchphrase among the Pilots. Player 1: "I only had 3 beers last night." Player 2: "Yeah, surrre!"

He also mentioned that married players fooled around. He later said that he never named names, not once. This was a half-truth. He mentioned that Oyler had once told his teammates, as they got off the plane at the end of a roadtrip, "Okay, all you guys: Act horny." And he mentioned that 1st baseman Mike Hegan once said that the hardest part of being a ballplayer was "explaining to your wife why she needs a penicllin shot for your kidney infection." (In other words, it wasn't a kidney infection, it was what we then called "VD.")

Less salacious, but one of the funniest moments in the book told of a time when they were playing the Minnesota Twins, who went on to win the American League Western Division that season. They were going over the lineup, which including home run champion Harmon Killebrew, former batting champion Tony Oliva, and future batting champion Rod Carew. Whenever a name was mentioned, pitcher Gary Bell -- Jim's roommate, but soon to be traded -- said, "Smoke him inside." In other words, throw him inside fastballs.

Every. Single. Hitter. Bell said, "Smoke him inside." Nobody laughed. Everybody took it seriously, Marshall pitched brilliantly and won the game, and Jim said, "I guess Mike Marshall smoked them on the inside."

The Pilots had talent. Outfielder and former National League batting champion Tommy Davis. 1st baseman Don Mincher, who had helped the Twins win the 1965 Pennant. Pitchers Bouton, Talbot, and Steve Barber, who had helped the Baltimore Orioles win the 1966 World Series. But injuries (including Barber's remark, "My arm's not sore, it's just a little stiff"), Schultz's bad managing, and Milkes' penny-pinching doomed the team to a 64-98 finish, last place.

Apparently, it wasn't just Milkes being a typical baseball GM of the time, cheap as hell for the sake of greed. Owners Max and Dewey Soriano, brothers, really couldn't afford to buy the team and keep it going. At the end of Spring Training 1970, they finally gave up, and sold the team to Milwaukee car dealer Bud Selig, who quickly got permission to move them, and a week later, they debuted in the regular season as the Milwaukee Brewers.

The fact that the team's operation was so ridiculous, that they only existed for that 1 season, and that the current Seattle team, debuting in 1977, is named the Mariners, not the Pilots, makes Ball Four seem like a novel, like the Pilots never actually existed. But they did.

In a 2000 interview with baseball historian Rob Neyer for ESPN.com, Jim, unaware of my assessment, backed it up:

The Pilots existed for only one year. It's almost a magical story. They're like "Brigadoon." It's a Major League Baseball team that, in many respects, exists only within the pages of a book. It's like a fictional baseball team, so the characters in the book have almost become like fictional characters.

And they were perfect for the book. It was gold. Everyone one of those players was an interesting story, in one way or another. You had rookies, and you had grizzled veterans...

It was a perfect cast of characters, almost as if somebody had said, "This team's not going to win any games, but if someone writes a book, this'll be a great ballclub."

By the time that they moved, Jim was long gone. On August 24, the Pilots traded him to the Houston Astros, for his former Yankee teammate, the Dooley Womack, and Roric Harrison, whose 140 major league appearances were all yet to come.

The difference was huge: Jim went from a dysfunctional 1st-year expansion team trying to stay out of last place, in a 30-year-old but already antiquated ballpark, in front of an average of 8,400 fans a night; to an 8th-year team in its 1st Pennant race (but they tailed off in September, finishing 81-81), in the then-modern Astrodome, in front of 18,000 much more enthusiastic fans a night.

Moreover, his teammates, including future Hall-of-Famer Joe Morgan and All-Star pitcher Larry Dierker, seemed to like him more. Even Tommy Davis, traded from the Pilots to the Astros a few days later, seemed to like him more in Houston than in Seattle. And manager Harry Walker, an All-Star center fielder on the 1940s Cardinals dynasty, trusted him with a start just 2 days into his Astro tenure, and gave him regular relief appearances.

For the 1969 Pilots: Jim made 57 appearances, but only 1 start, was 2-1, with 1 save, a 3.91 ERA, an ERA+ of 92, and a 1.250 WHIP. For the 1969 Astros, Jim made 16 appearances, but only 1 start, was 0-2, with 1 save, a 4.11 ERA, an ERA+ of 87, and a 1,435 WHIP. He was appearing about as often -- 1 game every 2.42 days in Seattle, every 2.50 days in Houston -- and not pitching as well in Houston, despite pitching in the pitcher-friendly Astrodome. Yet he was trusted more by the Astro organization.

When the season was over, Jim thought about Jim O'Toole, a member the starting rotation on the Pennant-winning 1961 Reds. They began Spring Training together with the Pilots, with, one would think, an even chance. But Jim was pitching, perhaps not well, but pitching, for a team that had been in a Pennant race; while O'Toole had only been able to hook up with a "semi-pro" team in his native Kentucky. Jim wondered if that would be him someday, and predicted that it would.

And he closed the book with these words: "I went down deep and the answer I came up with was yes. Yes, I would. You see, you spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time."

*

Jim began the 1970 season on the Astros' big-league roster, and things seemed to be going, if not especially well, then at least smoothly. Then came May, and Look magazine published an excerpt from Ball Four. The excerpt included the sensational "Mantle wasn't such a great guy" part. (The magazine went out of business the next year. No, I'm not blaming Jim Bouton for that.)

The public reaction was horrible. Jim was booed in every ballpark. When they played the Cincinnati Reds, Pete Rose yelled from one dugout to the other, "Fuck you, Shakespeare!"

When the Astros came into New York to play the Mets, Daily News sports columnist Dick Young, once liberal but grown conservative and nasty in his middle age -- his backstab of Tom Seaver on behalf of Mets management was yet to come -- wrote that Jim had become "a social leper." That night, before the game, Dick came to Jim, and Jim said the comment didn't bother him. Dick said, "I'm glad you didn't take it personally." That became the title of Jim's sequel book.

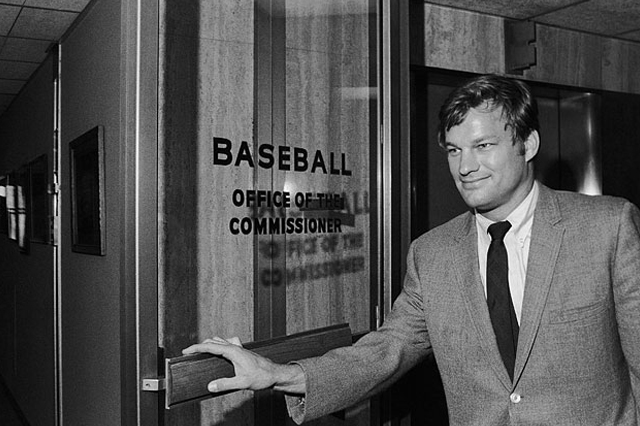

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn summoned Jim to his Midtown office. He told Jim to disavow the book before it could be published in full form, say that he'd made a lot of it up, or that Shecter had made a lot of it up, or that Shecter had manipulated into saying it.

Jim refused to lie, and wouldn't back down. He said it was all true. He said that any player whose marriage was now on the rocks because of what he wrote was probably not particularly strong anyway. He said that he didn't name names when it came to actually cheating on wives (despite the remarks of Oyler and Hegan).

He struck back, and said that he purposely left a lot of things out, like certain players going for underage girls, or spouting racist and anti-Semitic remarks, and that he was actually trying to protect the sport from what would have happened had he named names with such things.

That just deepened the baseball establishment's anger toward him. He had just gone even further in violating what had become known as "the sanctity of the clubhouse." There was a sign in most clubhouses: "What you see here, what you hear here, what you say here, let it stay here when you leave here." Jim wondered what "sanctity" there was in a room where men changed from street clothes to baseball uniforms and back again.

That was why the players were angry at him. The team owners were angry at him because he depicted them as greedy and petty, revealing their secrets to keeping salaries low -- in his words, because, "I was showing just how hard it was to make a living in baseball."

It was the Spring of 1970. The Beatles and the Supremes had broken up. The Kent State Massacre had happened, and a "Hard Hat Demonstration" in support of the Vietnam War was held in New York. Star Trek and The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour had been canceled, Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In had lost its momentum, and Woodstock had been followed by Altamont. No one wanted to hear about how baseball players were foul-mouthed sex fiends who might not have been 100 percent behind our boys in uniform.

America had decided that it couldn't handle the truth, and Jim Bouton was telling it.

He said the backlash wasn't getting to him. But on July 29, with a record of 4-6 and an ERA of 5.40, despite having pitched decently in 9 of his last 11 outings, he was sent down to the minor leagues. The knuckleball didn't work there, either.

Finally, Jim got an interesting offer: Al Primo, inventor of the "Eyewitness News" format, had gone to WABC-Channel 7 in New York, and wanted Jim, with his willingness to tell the truth and use his sense of humor, to be his sports anchor. On August 12, the Astros, probably glad to be rid of the bad publicity, gave Jim his unconditional release, and he spent the next 5 years doing sports behind anchors Roger Grimsby and Bill Beutel.

He then switched to WCBS-Channel 2, and his move to CBS allowed for a sitcom version of Ball Four. Jim, TV critic Marvin Kitman and sportswriter Vic Ziegel, then with the New York Post, created the series, about the fictional Washington Americans. Harry Chapin wrote and sang a theme song for it. (It wasn't Jim's 1st acting role: He had played killer Terry Lennox in the 1973 version of Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe story, The Long Goodbye.)

Anybody who had read the book recognized the players: Jim played pitcher Jim Barton, obviously based on himself; Jack Somack was the manager, Cap Capogrosso, based on Joe Schultz; Bill McCutcheon was coach Pinky Pinkney, clearly based on Frank Crosetti; and football player turned actor Ben Davidson was pitcher Rhino Rhinelander, based on the similarly large Gene Brabender.

The show debuted on September 22, 1976... and only aired 5 episodes. By this point, other tell-all baseball books having been released, making Jim's book look tame. But while the show tried to do for sports shows what All In the Family had done for family sitcoms and M*A*S*H had done for military shows, the audience had become desensitized to things like that. What was once shocking had become passe.

One of the later tell-all books was Home Games, written by Bobbie Bouton and Nancy Marshall, ex-wives of Jim and Mike, and published in 1983. Although Jim and Bobbie had 2 children together, son Michael and daughter Laurie, and had adopted a Korean boy named Kyong Jo, who anglicized his name to David, Bobbie claimed that Jim had fooled around on the road, and that the marriage finally ended because of it.

Jim didn't raise much of a fuss over it, saying, "We all have the right to write about our lives, and she does, too. If the book is insightful, if it helps people, I may be applauding it."

He added, "I'm sure most of the things she says are true. I smoked grass. I ran around. I found excuses to stay on the road."

*

Playing a ballplayer in the ill-fated TV version of Ball Four reminded Jim of the way baseball had "gripped" him. He left TV journalism, and announced a comeback. At the dawn of the 1977 season, he was signed as a free agent by the Chicago White Sox. But he couldn't get the knuckleball to work, and so he was released less than 2 months later.

He then went back to the Pacific Northwest, and signed with the Portland Mavericks, in the Class A Northwest League. Getting the knuckleball to work again, he did well enough there that Ted Turner signed him to a contract with the Atlanta Braves. Jim was assigned to the Savannah Braves of the Class AA Southern League, and did well enough there to become a September callup. He had become, in his own words, the 1st player to make the major leagues twice.

On September 10, 1978, at age 39, he put on Braves uniform Number 56, took the mound at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, started against the defending National League Champion Los Angeles Dodgers, and went 5 innings, allowing 6 runs, and ended up as the losing pitcher.

Four days later, the experiment was redeemed: He started against the San Francisco Giants at Candlestick Park, allowed 1 run, unearned, in 6 innings, and the Braves beat the Giants 4-1. He had gone without a major league win between July 11, 1970 and September 14, 1978. Had blogging been possible then, it would have made a good "How Long It's Been" piece.

He made 3 more starts: A no-decision against the Astros in Houston, a tough loss to the Reds in Atlanta, and a battering against the Reds in Cincinnati. That was on September 29, 1978, his true major league finale.

He had made his point -- but an unintended consequence of his comeback was that he fell below .500 for his career: His 1978 record of 1-3 (with an ERA of 4.97, an ERA+ of 83, and a WHIP of 1.586) dropped him, lifetime, from 61-60 to 62-63. His final ERA was 3.57, his ERA+ 99, his WHIP 1.264.

*

Jim wrote about his comeback in time for the 10th Anniversary of his book, titling the expanded edition Ball Four Plus Ball Five. He also edited an anthology about a subject he knew well, bad baseball managers: I Managed Good, But Boy Did They Play Bad. He fulfilled his prediction by pitching in North Jersey's Metropolitan Baseball League, a.k.a. the Met League, although he was quite a bit older than Jim O'Toole was when he was relegated to such leagues.

He returned to North Jersey, and married Paula Kurman, a psychologist. He and a former Portland teammate invented Big League Chew, a shredded bubblegum, which they concluded would be better for athletes than chewing tobacco. Jim probably made more money off that than he did playing ball. He joined with Eliot Asinof, author of Eight Men Out, the story of the 1919 Black Sox Scandal, to write Strike Zone, a novel that was part ballgame, part murder mystery.

In 1990, he published a 20th Anniversary edition, Ball Six, which included stories of how he'd reconciled with some of the Pilots, and how the Astros never really had a problem with him. But he hadn't yet reconciled with the Yankees. They'd never invited him back for Old-Timers' Day. His former Yankee and Astro teammate Joe Pepitone, who'd written a tell-all that made Jim's book look like a collection of nursery rhymes, and had done time on Riker's Island on a gun charge, had been invited back. So why not Jim?

Jim speculated that it was because he had made Mantle look bad in his book. Either Mickey was still mad at him from 1970, or the Yankee organization was worried that Mickey was. Either way, Number 7 was the reason Number 56 thought he hadn't been invited back.

In 1994, Mickey went to the Betty Ford Center to stop drinking. Shortly after he was released, his son Billy died of lymphoma. Jim sent Mickey a condolence card. Mickey, knowing that one of the things that recovering alcoholics should do is make amends for slights, both real and perceived, called Jim. Jim wasn't home, but he saved the message Mickey left. Mickey thanked him for the card, and said that he never asked the Yankees not to invite him back. (I believe him: Mickey was many things, some of them not so good, but he was never vindictive. Not like Joe DiMaggio.)

In 1997, Laurie Bouton, only 31 years old, was killed in a car crash. As Jim told in his 2000 version, Ball Four: The Final Pitch, on the 30th Anniversary of the original book, it devastated him. He included Paula's account of how it brought Jim and Bobbie back together, if not to be a couple again -- both had moved on to new marriages -- then to at least be in each other's lives again.

In 1998, with Old-Timers Day coming up, his son Michael Bouton wrote an open letter to the Yankees that was published in The New York Times, saying that, given the length of time, the death of Laurie, and Jim's absolution by Mickey, it was time to bring him back to Yankee Stadium.

On July 18, 1998, Yankee broadcaster Michael Kay made the introduction, and Jim Bouton ran onto the field at Yankee Stadium in a Pinstriped uniform Number 56 for the 1st time since the 1968 season. A crowd of 48,123 people, including yours truly, gave him a standing ovation. He even pitched to a batter in the Old-Timers Game. I don't know if he was using the knuckleball, but he did use his old motion, and let his cap fall off. (The Yankees won the regular game, beating the Toronto Blue Jays 10-3.)

In 1999, I attended a game between the New Jersey Jackals and the Massachusetts Mad Dogs at Yogi Berra Stadium in Little Falls, Passaic New Jersey. The stadium, and the adjoining Yogi Berra Museum, are on the campus of Montclair State University, not far from Yogi's home in Montclair, Essex County. (The campus straddles the 2 towns.) The Jackals got slaughtered. For me, the highlight of the game was the first ball, thrown out by Jim Bouton. I had a real close seat, and when it was over, he walked past me. We didn't shake hands or say anything, but we did both smile.

In 2000, Jim and Paula moved to Great Barrington, in the Berkshire Mountains of Western Massachusetts, a town famous for being the home of painter Norman Rockwell, and of folksinger Arlo Guthrie, the site of the events of his song "Alice's Restaurant."

The nearest professional baseball park was Wahconah Park in Pittsfield, home to various minor-league teams since 1919. After the 2003 season, the team that played there that season moved, leaving the old park without a tenant. It seemed to be doomed.

Jim decided that he would save Wahconah Park, renovating it without tax money and bringing a new pro team in. On July 3, 2004, at age 65, he pitched in a "vintage baseball" game that attracted over 5,000 fans. But the city council voted his proposal down, and he was defeated. He wrote about the struggle in the nonfiction book Foul Ball.

Maybe somebody in Pittsfield wanted to save the place, but not with Jim involved. In 2005, a new team was moved there, and a renovation was conducted for 2009. Since 2012, the Pittsfield Suns of the Futures Collegiate Baseball League, a Summer league for college-age players, have played there. So while Jim wasn't involved in the park's revival, he may well have made it possible. That's a win. Or, as he called a win in Ball Four, a "Big W."

Jim Bouton continued to promote old-time baseball with the Vintage Base Ball Federation, until 2012, when he suffered a stroke that damaged his memory and his ability to speak. It led to cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which slowly affected his mind and heart, until his death yesterday, July 10, 2019, at his home in Great Barrington, after having been released from hospice. The man known as Bulldog, Ass Eyes, Super Knuck, Shakespeare, Gyro Gearloose and Mr. Kurman was 80 years old.

Jim's playing career was interesting, but his book far exceeded it. It made him, and the other people mentioned in it, legends -- not always in good ways, but we're still talking about the 1969 Seattle Pilots, 50 years later. Is anybody still talking about the 1959 Washington Senators? About the 1965 Kansas City Athletics? About the 1973 Montreal Expos? Hardly anybody.

But people who've never been to Seattle, and people who were born well after 1969, are still saying, "Smoke him inside" and "Shitfuck" and "My arm's not sore, it's just a little stiff" and "THE Dooley Womack" and "Yeah, surrre!"

You see, we've spent a good piece of our lives gripping Jim Bouton's book Ball Four, and, in the end, it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.

Nobody had any idea of the impact that this book would have. It's almost as if the Major League Baseball pitching career that he had already had was becoming secondary. But then, as much as he loved baseball, Bouton was not all about it. He understood that it is often a microcosm of life, but it is not life and death.

James Alan Bouton was born on March 8, 1939, in Newark, New Jersey, and grew up in nearby Rochelle Park and Ridgewood, Bergen County. Jim and his brother Pete grew up as fans of the New York Giants baseball team. But when they were teenagers, the family moved from the suburbs of New York to the suburbs of Chicago, to Homewood, Illinois.

At this point, they would only get to see their heroes when they came to Wrigley Field to play the Chicago Cubs. On one such occasion, doing something that kids had been doing since the invention of dugouts, Pete held Jim by the legs, and he hung himself upside down over the visiting team dugout, pen in one hand, game program in the other, hoping to get an autograph from one of the Giants players.

He saw Alvin Dark, their shortstop and team captain, and said, "Hey, Al, my name's Jim, I'm not a Cub fan, I'm a Giant fan, I'm from New Jersey, can you sign my program, please?" After a minute, Pete pulled Jim back up, saw that he didn't get an autograph, and asked him what happened. Jim said Dark told him, "Take a hike, son."

Pete wasn't furious that a player had so coldly dismissed his brother. He was thrilled that a real live major league ballplayer had spoken to his brother: "No kidding? Alvin Dark told you to take a hike?"

When they got home, their mother asked them what happened. Rather than tell her who won, or about anything that happened in the actual game, Pete said, "Alvin Dark told Jim to take a hike!" After that, whenever someone in the Bouton family wanted to get rid of somebody, even if it was one of the parents, it would be, "Take a hike, Jim,""Take a hike, Mom," or, "Take a hike, Dad."

Jim was not a star pitcher in high school, hardly getting into a game, but always warming up for it, to the point where he was nicknamed "Warmup Bouton." It was a foreshadowing of the problem he would later face, as told in the pages of Ball Four. But in Summer leagues, he became a star, and got a baseball scholarship to Western Michigan University, in Kalamazoo. He was signed by the New York Yankees for $30,000.

When he reached the major leagues, he was given uniform Number 56, a very high number for the time. Later that season, clubhouse manager Pete Sheehy said he could now receive a smaller number, recommending 29. Jim said that he would rather keep 56, to remind him of just how difficult it is to stay in the major leagues.

He made his major league debut on April 22, 1962, at Yankee Stadium, pitching 3 innings in relief, without allowing a run. It didn't matter much, as the Yankees lost to the Cleveland Indians, 7-5. His next appearance was on May 6, in the 2nd game of a doubleheader against the Washington Senators. He went the distance, allowing 7 runs and 7 walks, but pitched a shutout in an 8-0 Yankee victory. After the game, he noticed a path of warm white towels from the clubhouse door to his locker. They were put there by Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford. Jim knew he had arrived.

When Mickey Mantle is willing to pose for a

picture with you, you know you've arrived.

Jim went 7-7 that year. The Yankees won the World Series, and he got a ring, but he did not appear in the Series. In 1963, just 24 years old, he went 21-7 with a 2.53 ERA, and made the All-Star Game for what turned out to be the only time. His fastball and gruff demeanor on the mound earned him the alliterative nickname "Bulldog" Bouton. Fans also loved that his unusual pitching motion caused his hat to frequently fly off his head.

He started Game 3 of the 1963 World Series, and pitched well, but Don Drysdale pitched better, and the Los Angeles Dodgers beat the Yankees 1-0, en route to a 4-game sweep. In 1964, he went 18-13, helping the Yankees win a tight Pennant race, and won Games 3 and 6 of the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, but the Yankees lost Game 7.

As Spring Training 1965 began, Jim was about to turn 26, and had good fastball, legendary teammates, and a career record of 46-27. But he hurt his elbow that year, one of many injuries that seemed to strike the old Yankee Dynasty at once. The Yankees finished 6th, and, for reasons that were almost entirely not his fault, Jim went 4-15.

That was when the nastier side of the old Yankees reared its head. When Jim was winning, his class clown antics got him labeled "colorful." His teammates didn't mind his intellectualism, his lefty politics, his outspokenness, or his impersonation of comedian Frank Fontaine in his "Crazy Guggenheim" role on The Jackie Gleason Show. But when he was losing, they acted like they didn't want to know him.

In Spring Training 1967, Jim was told, "You're having a better spring than Dooley Womack." Not wanting to rock the boat, he didn't say what he wanted to say, which was, "The Dooley Womack? I'm having a better spring than Whitey Ford or Mel Stottlemyre!" But he didn't have a good regular season. His fastball gone, he began experimenting with a knuckleball.

By 1968, the Dynasty was dead. On June 15, the Seattle Pilots, an expansion team that was going to begin play the next season, bought him from the Yankees, and assigned him to their top farm team, so that he could get work. As Spring Training came in 1969, he was about to turn 30, and he didn't know if he had enough left to make even a brand-new expansion team.

*

Another way that Jim was different was that he was friends with Leonard Shecter of the New York Post. Most Yankees hated him, because he was critical of them. Shecter was one of the "Chipmunks," the new breed of sportswriter who wasn't willing to accept the "Gee whiz, aren't these ballplayers all nice guys, virtuous guys who are good to kids, faithful to their wives, don't drink anything stronger than milkshakes, and only have pro-America and pro-God opinions" myth. Shecter thought that keeping the truth to yourself was not always a good idea.

The Yankees told Jim, "Don't talk to the reporters, especially that fuckin' Shecter." Jim wrote, "I heard 'fuckin' Shecter' so many times, I began to think that was his full name." But they became friends, and talked about the ballplayer image.

They agreed that most books "written by ballplayers" (always dictated to a sportswriter, who would arrange it so that it only made the player look good) were sappy, sanitized stories about the big names, and that it would be more interesting if a marginal player wrote a book about just how hard it was to make a living in baseball.

This was not a new idea: Jim Brosnan, a decent but not great pitcher, kept a diary in 1959, a season which saw him get traded from the Cardinals to the Cincinnati Reds. It was published as The Long Season, and got praise from some sources, and disdain from the baseball establishment, which presaged what Bouton would later go through. In 1961, Brosnan tried again, and was lucky that the Reds won the Pennant. That book was titled Pennant Race.

So there was precedent. Jim began writing notes at the Pilots' training camp in Tucson, Arizona. Just as he started writing, 2 things happened that would shape public perception of the book. One was that he negotiated his contract for the season, at a time when players were bound by baseball's reserve clause, which essentially bound them to a team for life, unless traded or released. He used the opportunity to describe his struggles to get what he thought he was worth from the Yankees.

The other big thing that happened was that Mickey Mantle retired, after 18 years of heroics and injuries. Jim told about how well Mickey had treated him. He also told about how Mickey could be juvenile and drunk, and not nice to young autograph seekers. (I wonder if he ever told any of them to "Take a hike, son.")

He also told about a combination of these phenomenons, Mickey leading Jim and some other young players onto the roof of the hotel they stayed at when they were playing the Washington Senators, an establishment now known as the Omni Shoreham. Because of the building's layout, the roof made it easy to be a Peeping Tom, watching women get dressed and undressed. Jim said the baseball term for this activity was "beaver shooting."

*

Jim made the team, but had 1 bad outing for the Pilots in April, and was sent down to the Vancouver Mounties of the Pacific Coast League. He was quickly brought back, but not used well. He began to see that he was never brought in during close games, only when the game was already out of hand, either way.

Jim Bouton in a Seattle Pilots uniform,

at Tiger Stadium in Detroit

He began to suspect that manager Joe Schultz, pitching coach Sal Maglie, and general manager Marvin Milkes didn't trust him, because he was an oddball throwing an oddball pitch (the knuckleball -- not the screwball).

Maglie had a case: He was once not just a great pitcher, with one of the best curveballs of his time, but a former New York Giant, and one of Jim's heroes. But Milkes was out of his depth as a baseball executive. And Schultz should have understood marginal players better, as he was one, a backup catcher in the 1940s, although he did help the St. Louis Browns win their only Pennant in 1944.

He was a coach on the Cardinals' 1960s Pennant winners, but he seemed to forget that he was no longer working for Cardinals owner and beer baron Gussie Busch. He was always telling his players, "Zitz 'em, and go pound some Budweiser!" He was a company man to the end.

Jim would plead his case for more appearances, even starts, and Joe would nod, munch on a liverwurst sandwich, and tell Jim what he wanted to hear, and then not do it. Schultz was fired after that season, and remained a coach in the majors through 1976, but never managed again except on an interim basis with the 1973 Detroit Tigers. (Jim said that Joe had 2 favorite words: "Shitfuck" and "Fuckshit.")

"Establishment" players on the Pilots, like shortstop Ray Oyler and pitcher Fred Talbot (a former Yankee teammate) tended to stay away from him. Other oddballs, like pitcher Mike Marshall and outfielder Steve Hovley, gravitated toward him.

Jim told a story about being invited to his former high school's sports awards banquet. He took questions. A kid stood up, and asked Jim what he thought about long hair. Jim said the problem wasn't that an entire generation of teenage boys decided to let their hair get longer, it was that schools were ready to expel otherwise well-behaved kids over it. The kids gave him a standing ovation. The parents, he said, resolved never to invite Jim Bouton again.

Jim wrote about silly pranks (such as convincing Talbot he'd won $5,000, and hitting another pitcher with a fake paternity suit), and juvenile activity (pitcher Marty Pattin doing an impression of Donald Duck giving pitching advice, Pattin doing Donald Duck having an orgasm, catcher Greg Goossen seeing a plaque on a building saying, "Erected in 1929," and saying, "That's quite an erection").

He mentioned drinking. Lots of lots of drinking. Including by Mantle, but also by the Pilots players. When Schultz told the team to report for a game at 10:30 AM, catcher Jim Pagliaroni said, "Ten-thirty? I'm not even done throwing up at that hour."

He mentioned amphetamine use, beginning a paragraph with, "How fabulous are greenies? The answer is very." He said that some players couldn't function without them. He said that they helped his performance maybe 5 percent, which wasn't enough. He told of a normally mild-mannered player who took a called 3rd strike, and then lit into the umpire. When the player returned to the dugout, he was asked, "What happened?" and he said, "My greenie kicked in." Jim told of another player, normally not a power hitter, who was jacking the ball out in batting practice. Someone asked, "What got into him?" And another player said, "Four greenies."

He mentioned a story that outfielder Jim Gosger told about hiding in the closet (with, apparently, no irony) while his roommate fooled around with a local groupie (they were called "baseball Annies"), who said she'd never done it that way before. Jim stuck his head out of the closet, and said, "Yeah, surrre!" (Jim wrote it with 3 R's.) From that point onward, it became a catchphrase among the Pilots. Player 1: "I only had 3 beers last night." Player 2: "Yeah, surrre!"

He also mentioned that married players fooled around. He later said that he never named names, not once. This was a half-truth. He mentioned that Oyler had once told his teammates, as they got off the plane at the end of a roadtrip, "Okay, all you guys: Act horny." And he mentioned that 1st baseman Mike Hegan once said that the hardest part of being a ballplayer was "explaining to your wife why she needs a penicllin shot for your kidney infection." (In other words, it wasn't a kidney infection, it was what we then called "VD.")

Less salacious, but one of the funniest moments in the book told of a time when they were playing the Minnesota Twins, who went on to win the American League Western Division that season. They were going over the lineup, which including home run champion Harmon Killebrew, former batting champion Tony Oliva, and future batting champion Rod Carew. Whenever a name was mentioned, pitcher Gary Bell -- Jim's roommate, but soon to be traded -- said, "Smoke him inside." In other words, throw him inside fastballs.

Every. Single. Hitter. Bell said, "Smoke him inside." Nobody laughed. Everybody took it seriously, Marshall pitched brilliantly and won the game, and Jim said, "I guess Mike Marshall smoked them on the inside."

The Pilots had talent. Outfielder and former National League batting champion Tommy Davis. 1st baseman Don Mincher, who had helped the Twins win the 1965 Pennant. Pitchers Bouton, Talbot, and Steve Barber, who had helped the Baltimore Orioles win the 1966 World Series. But injuries (including Barber's remark, "My arm's not sore, it's just a little stiff"), Schultz's bad managing, and Milkes' penny-pinching doomed the team to a 64-98 finish, last place.

Apparently, it wasn't just Milkes being a typical baseball GM of the time, cheap as hell for the sake of greed. Owners Max and Dewey Soriano, brothers, really couldn't afford to buy the team and keep it going. At the end of Spring Training 1970, they finally gave up, and sold the team to Milwaukee car dealer Bud Selig, who quickly got permission to move them, and a week later, they debuted in the regular season as the Milwaukee Brewers.

The fact that the team's operation was so ridiculous, that they only existed for that 1 season, and that the current Seattle team, debuting in 1977, is named the Mariners, not the Pilots, makes Ball Four seem like a novel, like the Pilots never actually existed. But they did.

In a 2000 interview with baseball historian Rob Neyer for ESPN.com, Jim, unaware of my assessment, backed it up:

The Pilots existed for only one year. It's almost a magical story. They're like "Brigadoon." It's a Major League Baseball team that, in many respects, exists only within the pages of a book. It's like a fictional baseball team, so the characters in the book have almost become like fictional characters.

And they were perfect for the book. It was gold. Everyone one of those players was an interesting story, in one way or another. You had rookies, and you had grizzled veterans...

It was a perfect cast of characters, almost as if somebody had said, "This team's not going to win any games, but if someone writes a book, this'll be a great ballclub."

By the time that they moved, Jim was long gone. On August 24, the Pilots traded him to the Houston Astros, for his former Yankee teammate, the Dooley Womack, and Roric Harrison, whose 140 major league appearances were all yet to come.

The difference was huge: Jim went from a dysfunctional 1st-year expansion team trying to stay out of last place, in a 30-year-old but already antiquated ballpark, in front of an average of 8,400 fans a night; to an 8th-year team in its 1st Pennant race (but they tailed off in September, finishing 81-81), in the then-modern Astrodome, in front of 18,000 much more enthusiastic fans a night.

Moreover, his teammates, including future Hall-of-Famer Joe Morgan and All-Star pitcher Larry Dierker, seemed to like him more. Even Tommy Davis, traded from the Pilots to the Astros a few days later, seemed to like him more in Houston than in Seattle. And manager Harry Walker, an All-Star center fielder on the 1940s Cardinals dynasty, trusted him with a start just 2 days into his Astro tenure, and gave him regular relief appearances.

Jim with the Houston Astros, 1969,

possibly at Crosley Field in Cincinnati

For the 1969 Pilots: Jim made 57 appearances, but only 1 start, was 2-1, with 1 save, a 3.91 ERA, an ERA+ of 92, and a 1.250 WHIP. For the 1969 Astros, Jim made 16 appearances, but only 1 start, was 0-2, with 1 save, a 4.11 ERA, an ERA+ of 87, and a 1,435 WHIP. He was appearing about as often -- 1 game every 2.42 days in Seattle, every 2.50 days in Houston -- and not pitching as well in Houston, despite pitching in the pitcher-friendly Astrodome. Yet he was trusted more by the Astro organization.

When the season was over, Jim thought about Jim O'Toole, a member the starting rotation on the Pennant-winning 1961 Reds. They began Spring Training together with the Pilots, with, one would think, an even chance. But Jim was pitching, perhaps not well, but pitching, for a team that had been in a Pennant race; while O'Toole had only been able to hook up with a "semi-pro" team in his native Kentucky. Jim wondered if that would be him someday, and predicted that it would.

And he closed the book with these words: "I went down deep and the answer I came up with was yes. Yes, I would. You see, you spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time."

*

Jim began the 1970 season on the Astros' big-league roster, and things seemed to be going, if not especially well, then at least smoothly. Then came May, and Look magazine published an excerpt from Ball Four. The excerpt included the sensational "Mantle wasn't such a great guy" part. (The magazine went out of business the next year. No, I'm not blaming Jim Bouton for that.)

The first edition hardcover

The public reaction was horrible. Jim was booed in every ballpark. When they played the Cincinnati Reds, Pete Rose yelled from one dugout to the other, "Fuck you, Shakespeare!"

When the Astros came into New York to play the Mets, Daily News sports columnist Dick Young, once liberal but grown conservative and nasty in his middle age -- his backstab of Tom Seaver on behalf of Mets management was yet to come -- wrote that Jim had become "a social leper." That night, before the game, Dick came to Jim, and Jim said the comment didn't bother him. Dick said, "I'm glad you didn't take it personally." That became the title of Jim's sequel book.

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn summoned Jim to his Midtown office. He told Jim to disavow the book before it could be published in full form, say that he'd made a lot of it up, or that Shecter had made a lot of it up, or that Shecter had manipulated into saying it.

Jim refused to lie, and wouldn't back down. He said it was all true. He said that any player whose marriage was now on the rocks because of what he wrote was probably not particularly strong anyway. He said that he didn't name names when it came to actually cheating on wives (despite the remarks of Oyler and Hegan).

Like Muhammad Ali, Tommie Smith and Curt Flood

at the time, and like Colin Kaepernick many years later,

Jim was willing to stand for something,

even if it meant sacrificing everything.

That just deepened the baseball establishment's anger toward him. He had just gone even further in violating what had become known as "the sanctity of the clubhouse." There was a sign in most clubhouses: "What you see here, what you hear here, what you say here, let it stay here when you leave here." Jim wondered what "sanctity" there was in a room where men changed from street clothes to baseball uniforms and back again.

That was why the players were angry at him. The team owners were angry at him because he depicted them as greedy and petty, revealing their secrets to keeping salaries low -- in his words, because, "I was showing just how hard it was to make a living in baseball."

It was the Spring of 1970. The Beatles and the Supremes had broken up. The Kent State Massacre had happened, and a "Hard Hat Demonstration" in support of the Vietnam War was held in New York. Star Trek and The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour had been canceled, Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In had lost its momentum, and Woodstock had been followed by Altamont. No one wanted to hear about how baseball players were foul-mouthed sex fiends who might not have been 100 percent behind our boys in uniform.

America had decided that it couldn't handle the truth, and Jim Bouton was telling it.

He said the backlash wasn't getting to him. But on July 29, with a record of 4-6 and an ERA of 5.40, despite having pitched decently in 9 of his last 11 outings, he was sent down to the minor leagues. The knuckleball didn't work there, either.

Finally, Jim got an interesting offer: Al Primo, inventor of the "Eyewitness News" format, had gone to WABC-Channel 7 in New York, and wanted Jim, with his willingness to tell the truth and use his sense of humor, to be his sports anchor. On August 12, the Astros, probably glad to be rid of the bad publicity, gave Jim his unconditional release, and he spent the next 5 years doing sports behind anchors Roger Grimsby and Bill Beutel.

He then switched to WCBS-Channel 2, and his move to CBS allowed for a sitcom version of Ball Four. Jim, TV critic Marvin Kitman and sportswriter Vic Ziegel, then with the New York Post, created the series, about the fictional Washington Americans. Harry Chapin wrote and sang a theme song for it. (It wasn't Jim's 1st acting role: He had played killer Terry Lennox in the 1973 version of Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe story, The Long Goodbye.)

Anybody who had read the book recognized the players: Jim played pitcher Jim Barton, obviously based on himself; Jack Somack was the manager, Cap Capogrosso, based on Joe Schultz; Bill McCutcheon was coach Pinky Pinkney, clearly based on Frank Crosetti; and football player turned actor Ben Davidson was pitcher Rhino Rhinelander, based on the similarly large Gene Brabender.

The show debuted on September 22, 1976... and only aired 5 episodes. By this point, other tell-all baseball books having been released, making Jim's book look tame. But while the show tried to do for sports shows what All In the Family had done for family sitcoms and M*A*S*H had done for military shows, the audience had become desensitized to things like that. What was once shocking had become passe.

One of the later tell-all books was Home Games, written by Bobbie Bouton and Nancy Marshall, ex-wives of Jim and Mike, and published in 1983. Although Jim and Bobbie had 2 children together, son Michael and daughter Laurie, and had adopted a Korean boy named Kyong Jo, who anglicized his name to David, Bobbie claimed that Jim had fooled around on the road, and that the marriage finally ended because of it.

Jim didn't raise much of a fuss over it, saying, "We all have the right to write about our lives, and she does, too. If the book is insightful, if it helps people, I may be applauding it."

He added, "I'm sure most of the things she says are true. I smoked grass. I ran around. I found excuses to stay on the road."

*

Playing a ballplayer in the ill-fated TV version of Ball Four reminded Jim of the way baseball had "gripped" him. He left TV journalism, and announced a comeback. At the dawn of the 1977 season, he was signed as a free agent by the Chicago White Sox. But he couldn't get the knuckleball to work, and so he was released less than 2 months later.

He then went back to the Pacific Northwest, and signed with the Portland Mavericks, in the Class A Northwest League. Getting the knuckleball to work again, he did well enough there that Ted Turner signed him to a contract with the Atlanta Braves. Jim was assigned to the Savannah Braves of the Class AA Southern League, and did well enough there to become a September callup. He had become, in his own words, the 1st player to make the major leagues twice.

On September 10, 1978, at age 39, he put on Braves uniform Number 56, took the mound at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, started against the defending National League Champion Los Angeles Dodgers, and went 5 innings, allowing 6 runs, and ended up as the losing pitcher.

Four days later, the experiment was redeemed: He started against the San Francisco Giants at Candlestick Park, allowed 1 run, unearned, in 6 innings, and the Braves beat the Giants 4-1. He had gone without a major league win between July 11, 1970 and September 14, 1978. Had blogging been possible then, it would have made a good "How Long It's Been" piece.

A mockup of a baseball card that never was

He made 3 more starts: A no-decision against the Astros in Houston, a tough loss to the Reds in Atlanta, and a battering against the Reds in Cincinnati. That was on September 29, 1978, his true major league finale.

He had made his point -- but an unintended consequence of his comeback was that he fell below .500 for his career: His 1978 record of 1-3 (with an ERA of 4.97, an ERA+ of 83, and a WHIP of 1.586) dropped him, lifetime, from 61-60 to 62-63. His final ERA was 3.57, his ERA+ 99, his WHIP 1.264.

*

Jim wrote about his comeback in time for the 10th Anniversary of his book, titling the expanded edition Ball Four Plus Ball Five. He also edited an anthology about a subject he knew well, bad baseball managers: I Managed Good, But Boy Did They Play Bad. He fulfilled his prediction by pitching in North Jersey's Metropolitan Baseball League, a.k.a. the Met League, although he was quite a bit older than Jim O'Toole was when he was relegated to such leagues.

He returned to North Jersey, and married Paula Kurman, a psychologist. He and a former Portland teammate invented Big League Chew, a shredded bubblegum, which they concluded would be better for athletes than chewing tobacco. Jim probably made more money off that than he did playing ball. He joined with Eliot Asinof, author of Eight Men Out, the story of the 1919 Black Sox Scandal, to write Strike Zone, a novel that was part ballgame, part murder mystery.

In 1990, he published a 20th Anniversary edition, Ball Six, which included stories of how he'd reconciled with some of the Pilots, and how the Astros never really had a problem with him. But he hadn't yet reconciled with the Yankees. They'd never invited him back for Old-Timers' Day. His former Yankee and Astro teammate Joe Pepitone, who'd written a tell-all that made Jim's book look like a collection of nursery rhymes, and had done time on Riker's Island on a gun charge, had been invited back. So why not Jim?

Jim speculated that it was because he had made Mantle look bad in his book. Either Mickey was still mad at him from 1970, or the Yankee organization was worried that Mickey was. Either way, Number 7 was the reason Number 56 thought he hadn't been invited back.

In 1994, Mickey went to the Betty Ford Center to stop drinking. Shortly after he was released, his son Billy died of lymphoma. Jim sent Mickey a condolence card. Mickey, knowing that one of the things that recovering alcoholics should do is make amends for slights, both real and perceived, called Jim. Jim wasn't home, but he saved the message Mickey left. Mickey thanked him for the card, and said that he never asked the Yankees not to invite him back. (I believe him: Mickey was many things, some of them not so good, but he was never vindictive. Not like Joe DiMaggio.)

In 1997, Laurie Bouton, only 31 years old, was killed in a car crash. As Jim told in his 2000 version, Ball Four: The Final Pitch, on the 30th Anniversary of the original book, it devastated him. He included Paula's account of how it brought Jim and Bobbie back together, if not to be a couple again -- both had moved on to new marriages -- then to at least be in each other's lives again.

In 1998, with Old-Timers Day coming up, his son Michael Bouton wrote an open letter to the Yankees that was published in The New York Times, saying that, given the length of time, the death of Laurie, and Jim's absolution by Mickey, it was time to bring him back to Yankee Stadium.

On July 18, 1998, Yankee broadcaster Michael Kay made the introduction, and Jim Bouton ran onto the field at Yankee Stadium in a Pinstriped uniform Number 56 for the 1st time since the 1968 season. A crowd of 48,123 people, including yours truly, gave him a standing ovation. He even pitched to a batter in the Old-Timers Game. I don't know if he was using the knuckleball, but he did use his old motion, and let his cap fall off. (The Yankees won the regular game, beating the Toronto Blue Jays 10-3.)

In 1999, I attended a game between the New Jersey Jackals and the Massachusetts Mad Dogs at Yogi Berra Stadium in Little Falls, Passaic New Jersey. The stadium, and the adjoining Yogi Berra Museum, are on the campus of Montclair State University, not far from Yogi's home in Montclair, Essex County. (The campus straddles the 2 towns.) The Jackals got slaughtered. For me, the highlight of the game was the first ball, thrown out by Jim Bouton. I had a real close seat, and when it was over, he walked past me. We didn't shake hands or say anything, but we did both smile.

In 2000, Jim and Paula moved to Great Barrington, in the Berkshire Mountains of Western Massachusetts, a town famous for being the home of painter Norman Rockwell, and of folksinger Arlo Guthrie, the site of the events of his song "Alice's Restaurant."

Paula Kurman and Jim Bouton

The nearest professional baseball park was Wahconah Park in Pittsfield, home to various minor-league teams since 1919. After the 2003 season, the team that played there that season moved, leaving the old park without a tenant. It seemed to be doomed.

Jim decided that he would save Wahconah Park, renovating it without tax money and bringing a new pro team in. On July 3, 2004, at age 65, he pitched in a "vintage baseball" game that attracted over 5,000 fans. But the city council voted his proposal down, and he was defeated. He wrote about the struggle in the nonfiction book Foul Ball.

Maybe somebody in Pittsfield wanted to save the place, but not with Jim involved. In 2005, a new team was moved there, and a renovation was conducted for 2009. Since 2012, the Pittsfield Suns of the Futures Collegiate Baseball League, a Summer league for college-age players, have played there. So while Jim wasn't involved in the park's revival, he may well have made it possible. That's a win. Or, as he called a win in Ball Four, a "Big W."

Jim Bouton continued to promote old-time baseball with the Vintage Base Ball Federation, until 2012, when he suffered a stroke that damaged his memory and his ability to speak. It led to cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which slowly affected his mind and heart, until his death yesterday, July 10, 2019, at his home in Great Barrington, after having been released from hospice. The man known as Bulldog, Ass Eyes, Super Knuck, Shakespeare, Gyro Gearloose and Mr. Kurman was 80 years old.

Jim's playing career was interesting, but his book far exceeded it. It made him, and the other people mentioned in it, legends -- not always in good ways, but we're still talking about the 1969 Seattle Pilots, 50 years later. Is anybody still talking about the 1959 Washington Senators? About the 1965 Kansas City Athletics? About the 1973 Montreal Expos? Hardly anybody.

But people who've never been to Seattle, and people who were born well after 1969, are still saying, "Smoke him inside" and "Shitfuck" and "My arm's not sore, it's just a little stiff" and "THE Dooley Womack" and "Yeah, surrre!"

You see, we've spent a good piece of our lives gripping Jim Bouton's book Ball Four, and, in the end, it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.